by Christopher J. Bruce and Jody Prevost

The cost of hiring individuals to perform household services such as housecleaning, snow removal, and handyman repairs can amount to a significant percentage of the damages in a personal injury or fatal accident claim. Yet, despite the importance of these costs, reliable estimates of the components of a household services claim are very difficult to obtain. In order to assist the court in this respect, Economica has conducted a number of surveys of household services costs since 1997.

In those surveys, for example, we found that the average hourly cost of housecleaners in Calgary rose from approximately $13.50 in 1997, to $30.00 in 2014; and for handymen the rates rose from $24.00 in 1997 to $35.00 in 2014.

As four years have passed since our last survey, and as our experience suggests that rates tend to increase appreciably over time, we undertook a new survey of providers in 2018. In each case, we conducted exhaustive searches of relevant quotes using Kijiji and Google (the two most common sources of advertisements). This article summarises our findings.

Housecleaning

Using the internet, we identified sixteen professional agencies (for example, Mango Maids) in Calgary and fourteen in Edmonton that provide house cleaning; and we identified six ads from individuals (on Kijiji) in Calgary and seven in Edmonton.

In Calgary, the average rate among professional agencies was $41.38 per hour, with a range from $25.00 to $56.80. The comparable average for Edmonton was $39.28, ranging from $25.00 to $65.66. Among those individuals who advertised on sites such as Kijiji, the average hourly rate in Calgary was $26.67 and in Edmonton was $30.57.

In the smaller cities, most of our data came from Kijiji. In those cities, the average hourly rates (with numbers of ads in brackets) were: Lethbridge (6), $29.16; Red Deer (7), $29.71; Medicine Hat (5), $29.00; and Grande Prairie (7), $29.30.

We conclude that rates for individual suppliers average approximately $29.00 per hour across all Alberta cities; and that comparable rates for professional agencies average approximately $40.00 per hour (where such services are available).

These data raise two important question: first, if individuals listed on Kijiji charge approximately $29 per hour, why do consumers hire professional agencies at $11 per hour more than that? Second, why do the rates for individual suppliers exceed the hourly wages paid to individuals who work for professional agencies?

Professional agencies versus individuals

We suspect that the answer to the first of these questions derives from three factors.

First, agencies may be able to offer a higher quality of service than can private individuals. For example, they might provide training to their employees, use screening interviews to select the most skilled workers, or offer to replace workers who proved to be unacceptable to the client.

Second, it is possible that agencies might be able to complete their tasks more quickly than would private contractors, thereby lowering the effective hourly rate of the former.

Finally, commercial firms may be better able than individual cleaners to develop reputations for reliable service. If a cleaner is sick or otherwise unable to work, a firm can often replace that individual with another employee; whereas if self-employed individuals are unable to meet their commitments, their jobs go undone. Customers may be willing to pay a premium for the more reliable service.

Regardless of the answer to this question, however, the fact is that it would be very difficult to hire a reliable housecleaner in Calgary or Edmonton for less than $30 per hour – and that cost would rise to more than $40 per hour if the client wished to hire a bonded cleaning service.

Self-employed suppliers versus employees

A second puzzle raised by our findings is that, according to the Alberta Wage and Salary Survey, “light duty cleaners” earned an average of $16.08 per hour in 2017, with a range of $12.75—$20.13, more than $10.00 per hour less than the rates charged by individuals advertising on Kijiji. What is the source of this differential? One possibility is that the individuals identified by the Survey are working as employees for large cleaning companies and, therefore, have security of employment; whereas those advertising on Kijiji are self-employed, with the attendant uncertainties and with the requirement, in many cases, that they provide their own cleaning supplies. Another possibility is that it is the more productive, reliable individuals who choose self-employment. Regardless of the answer, our evidence suggests that individual plaintiffs will not be able to hire housecleaners at the wage found in the Alberta Wage and Salary Survey. It is the rates found on Kijiji and on the websites of professional agencies that best reflect the cost of hiring a housecleaner for an hour.

A caveat

It should be noted, however, that even if it costs, say, $30 to hire a housecleaner for one hour, it does not follow that it will cost $30 to replace one hour of a plaintiff’s time. The reason for this is that professional cleaners may be able to complete more work in an hour than could non-professionals (i.e. than plaintiffs). The best information we have available, for example, suggests that this differential is approximately 25 percent; that is, to replace one of the plaintiff’s hours will require only 0.75 hours of a professional’s time. In this case, the cost of replacing an hour will be $22.50 (= 0.75 x $30). [Note: this argument with respect to the greater efficiency of professional providers applies to all of the other services identified in this report, except child care.]

Handyman

With respect to handyman services, we obtained quotes from Yelp, Google and Kijiji. In each case, we requested a quote to “replace several fence boards, clean and repair the gutters, and paint the step rails and trim.”

In Calgary, where we received responses from four individuals and five professional companies, the average hourly rate was $45.28. Three companies had minimum charges of two hours.

In Edmonton, where we received responses from six professional companies and four individuals, the average hourly rate was $47.50. Only two companies specified a minimum number of hours billed.

In both cities, the preponderance of quotes fell between $40.00 and $50.00.

Lawn care and snow removal

Lawn care

In our search for lawn care rates in Calgary and Edmonton we asked for quotes for a 2400 square foot lot with an 1800 square foot house, front and back. Of sixteen lawn care companies surveyed in Calgary, fifteen ads were from professional companies and one from an individual. In Edmonton, of fourteen lawn care companies surveyed, eleven were from professional services and three from individuals.

In Calgary the average cost was $36.73 per visit for lawn care and $200 per month for lawn cutting. In Edmonton these rates were $46.63 and $157.80, respectively.

Snow removal

With respect to snow removal, we surveyed businesses in Calgary and Edmonton for quotes to remove snow from a home with a two-car driveway, stairs, entry, and city sidewalk.

Twelve companies in Calgary responded, with an average per visit rate of $36.33 and a monthly “unlimited” rate of $176.05. In Edmonton, eleven companies responded, with an average per visit rate of $41.14 and a monthly “on demand program” of $182.05.

Child care

We identified six methods of providing (commercial) child care: day care, day home, live-in nanny, live-out nanny, before- and after-school care, and (hourly) babysitting. We obtained all of our information from Google and kijiji.

Day homes

We identified six day homes in Calgary and nine in Edmonton. In Calgary, the rates averaged $57.50 per day, or $845 per month; whereas the comparable rates in Edmonton were $45 per day, or $759 per month.

Day care

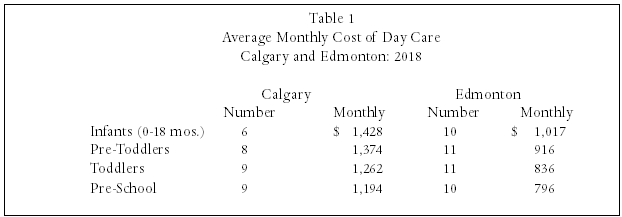

Our findings with respect to the monthly cost of day care are reported in Table 1. There, we provide rates by four age groups: infants (0 to 18 months), pre-toddlers (18-24 months), toddlers (24-36 months) and pre-school (four and five years).

Before- and after-school care

The average monthly rate for before- and after-school care, for children in grades one to six, was found to be $532 per month in Calgary (nine agencies) and $603 in Edmonton (six agencies).

Nannies

The average monthly rate for the three live-in nannies we identified in Calgary was $2,466, and for three live-out nannies it was $3,200. We also obtained hourly rates, averaging $17.50 (approximately $3,500 per month) for fifteen live-out nannies in Calgary.

In Edmonton, the monthly rate for the six live-in nannies we identified was $2,300; and for the five live-out nannies in our survey it was $2,600. We were also able to obtain hourly wages for fifteen live-in and fifteen live-out nannies in Edmonton. The average rates for those samples were $16.00 and $16.47, respectively (approximately $3,200 and $3,300 per month, respectively).

Babysitting

In each of Calgary and Edmonton, we obtained twenty quotes for babysitting services. In each city, eleven of the quotes came from Kijiji and nine came from a website called nannyservices.ca. The average hourly quote from Kijiji was $14.55 in Calgary and $13.23 in Edmonton. The average quote from nannyservices was $15.77 in Calgary and $16.33 in Edmonton. In both cities and for both sources, the most common rate was $15 per hour. (The slightly higher rate from nannyservices appears to have arisen because many of the individuals advertising on that site offered ancillary services such as dog walking and light housekeeping.)

Home care and meal preparation

Generalized home care services range in price by the level of assistance required. We obtained information from five professional agencies in Calgary and Edmonton – Home Care Assistance Calgary, Miraculum Home Care, Wild Rose Caregivers, Classic Life Care, and Paramed Home Health – concerning the costs of caring for “a relative that had been injured in an accident and was recuperating at home”.

Home Care Assistance Calgary provided quotes for both daily and monthly care for: meal preparation, light housekeeping, grocery shopping, grooming and dressing, bathing assistance and in some cases medical assistance. Their rates were $128 per day for part-time care and $256 per day for full-time care. Weekly rates varied from $384 to $1,792; and monthly rates from $1,164 to $7,765, depending on the number of hours required.

We found that hourly rates for the five agencies varied according to the qualifications of the workers who were required. Health care aides cost from $27 to $32 per hour; licensed practical nurses approximately $37 per hour; and registered nurses approximately $60 per hour.

We also obtained rates from individuals advertising on the website nannyservices.ca. Searching under companion and health care aide, we found that health care aides and personal service workers charge an average hourly rate of $21 in Calgary and $18 in Edmonton. In both cities, full time services cost $2,800 per month.

Summary

In this article, we have reported the results of a survey of household services providers in Alberta. Two outcomes are very clear. First, it is inappropriate to use a single, hourly rate to evaluate all such services. Whereas child care services cost less than $10 per hour, ($45 to $57 per day), housecleaning services cost almost $30 per hour, and lawn care and snow removal cost over $35 per visit.

Second, the convention of using $12 to $16 per hour for household services is unsupportable. With the exception of child care, all of the services that were identified in our survey cost significantly more than that, even after allowing for the greater efficiency of professionals.

Our findings also strongly support the view that hourly rates for housekeeping services should not be obtained by simply averaging the figures that have been adopted in previous cases. We are pleased to note that Madame Justice D. C. Read agreed with our conclusion on the latter point in her decision in Palmquist v. Ziegler, 2010 ABQB 337, at para [271] (emphasis added):

By using an average of numbers accepted in other cases in order to establish a number used to make an assumption in this case, all of the possible errors, either of the trial judge or of the economists who gave evidence in those cases, are incorporated into the number to be used in this case. Courts rely upon economists to determine what assumptions are reasonable to make and their decisions are only as reasonable as are the assumptions used. I have no means of evaluating the expert evidence that was before those other courts to determine whether or not I accept the assumptions made. It is circular to accept that an average of numbers accepted by another courts has any validity in respect to the issue of what economic assumptions are reasonable for me to make in this case.

Proposal

Statistics Canada provides data concerning the amounts of time spent on six types of “household work and related activities.” These are: cooking/washing up, house cleaning and laundry, maintenance and repair, other household work, shopping for goods and services, and primary child care. For the purposes of calculating the costs of household services, in our reports we will combine “cooking/washing up” with “shopping” and evaluate that category at the approximate average rate for home care and meal preparation, $32.00 per hour (up from $25.00 per hour in our 2014 survey).

We will combine “maintenance and repair” with “other household work” (a large portion of which consists of “gardening and ground work”) and evaluate the resulting services at the landscaping, snow removal, and handyman services rate of approximately $38.00 per hour (up from $35.00 in 2010).

We will evaluate “house cleaning and laundry” at the rate for housecleaning services. For the purposes of our reports, we propose to use the conservative rate of $29.00 per hour in all regions of Alberta (down from $30 per hour in Calgary and Edmonton in 2014, but up from $25.00 per hour elsewhere).

For each of the preceding services, however, we will assume that professionals will be 25 percent more efficient than the plaintiff would have been. Hence, our assumption is that the cost of those services is 25 percent less than the rate that has been quoted per hour.

We will assume that it in Calgary it costs $1,200 per month to care for each infant (the approximate mid-point of day care and home care costs), or $900 in Edmonton; $1,000 to care for each toddler/pre-school child in Calgary, ($800 in Edmonton); and $525 per month to provide before- and after-school care for each school-aged child in Calgary ($600 in Edmonton).

Finally, for the purposes of quantifying child care costs on an hourly basis, we propose to employ $15.00 per hour, (the most common rate quoted for babysitting in Calgary and Edmonton).

Christopher Bruce is the President of Economica; he has a PhD in economics from the University of Cambridge

Jody Prevost is the administrative assistant at Economica