by Christopher J. Bruce, Derek W. Aldridge, Kelly Rathje, Laura Weir

When calculating the lump sum award that is to replace a stream of losses in the future, it is first necessary to determine the rate of interest, or discount rate, at which the award will be invested. In Canada, this rate is set equal to the real rate of interest, that is, to the nominal (or “observed”) interest rate net of the rate of inflation.

Whereas most provinces mandate the discount rate that is to be used when calculating the present value of future losses, Alberta has left the determination of that rate to the courts. Accordingly, the testimony of financial experts on this matter has become an important element of most personal injury actions.

Over the last forty years, Economica has made important contributions to the debate concerning the choice of a discount rate. These contributions have come in the form of chapters in our textbook, Assessment of Personal Injury Damages (now in its fifth edition), articles in this newsletter, and submissions to reviews of the mandated rates in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia.

In this article, we argue that whereas virtually all financial experts (including ourselves) have implicitly applied what we will call here the active management approach to the determination of the discount rate, it can be argued that an alternative technique, which we will call the annuity approach, is often more appropriate.

In Section I of this article, we describe these two approaches and investigate their relative merits. In Section II, we employ the principles developed in the first section, to examine how numerical measures of the discount rate might be obtained when discounting two types of future costs: medical expenses and losses of earnings. Finally, in Section III, we summarise our findings.

In that Section, we argue that:

- if the plaintiff chooses to self-manage the investment of his or her award, the appropriate discount rate (net of inflation) is 2.5 percent; whereas

- if the plaintiff chooses to purchase a life annuity, or have the defendant purchase a structured settlement, the appropriate discount rate (net of inflation) is zero percent. We argue that it is to the advantage of plaintiffs to make this choice in most cases in which their losses are expected to continue into ages of high mortality (usually after age 75 or so).

I. Two Approaches to Selecting the Discount Rate

There are two broad approaches to the determination of the discount rate, the annuity approach and the active management approach. In the former, it is assumed that plaintiffs will use their lump sum awards to purchase annuities. In the latter, it is assumed that they will invest their awards in a portfolio of stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other financial assets.

In this section, we define the two approaches and investigate their relative merits. We conclude by identifying the circumstances in which each approach might be preferred to the other.

1. The Two Approaches Defined

The Annuity Approach

If the plaintiff has been awarded a lump sum award to replace a stream of losses from the date of trial until some specified termination date – most often the plaintiff’s projected date of retirement or date of death – he or she will be able to replace the future losses by purchasing an annuity, usually from a life insurance company. This purchase can take the form of either a life annuity or, under the auspices of the court, a structured settlement. In either case, the plaintiff will receive a specified stream of benefits until the termination date.

The purchase price of the annuity will be determined by three main factors: the value of the annual payments, the number of years to the termination date (which will, in part, be determined by the life expectancy of the plaintiff), and the rate of interest at which the insurance company is able to invest the funds received from the plaintiff (or defendant, in the case of a structured settlement).

It is this rate of interest that is known as the discount rate. In the case of an annuity, the discount rate is determined primarily by the requirement (arising both from regulation and accepted accounting practices) that the stream of payments the insurance company has contracted to make is matched by the stream of income that the company will receive from its investment. That is, at the time the annuity contract is signed, the insurance company will invest a sufficient amount, in secure financial instruments, that the income generated from that investment will be sufficient to fund the stream of payments the company has contracted to pay.

What this implies is that for each promised future payment, the insurance company will, implicitly make a separate investment that will generate sufficient returns that it will be able to cover the contracted payment at the appropriate date. For example, if it has contracted to pay $50,000 per year for ten years, it will make ten separate investments, each of which has a maturity value of $50,000.

The discount rate applicable to the payment that must be made one year from now is the interest rate currently available on one-year investments (such as one-year bonds); the rate applicable to the payment to be made two years from now is the interest rate currently available on two-year investments; etc. Thus, there could, in principle, be as many discount rates as there are time periods in the plaintiff’s stream of losses. (In practice, however, investments for more than ten or fifteen years tend to have the same interest rate, so a thirty-year annuity might require ten discount rates.)

Note, first, that there is not “a” discount rate. Rather, there is one rate for each year over which the stream of payments is to be made into the future.

More importantly, note also that it is not necessary to “predict” the discount rate(s). As the investments are to be purchased today (i.e. at the date of settlement), it is the interest rates that are available today that are to be used – and these rates are readily available.

Structured settlement: If it is assumed that a structured settlement is to be purchased, the argument concerning choice of a discount rate is similar to that for a life annuity. Again, the insurance company will place the lump sum received from the defendant in a series of investments, each of which will mature on the date that the payment is due. As the insurance company can be expected, once again, to purchase secure investments, the rates of return that are currently available on such investments can be used to determine the discount rate(s).

The Active Management Approach

Alternatively, the plaintiff might use his or her award to purchase a mixed portfolio of financial assets – for example, stocks, bonds, and mutual funds – selling and buying components within that portfolio as changes occur in financial markets. Because the individual is continuously selling old investments and purchasing new ones, the returns on those investments will reflect rising (and falling) rates that are available in the financial markets.

The complication that this approach introduces is that the rates of return that will be available at the times the plaintiff reinvests his or her funds are not known at the time that the court award is made. These rates must be predicted – in contrast to the rates employed in the annuity approach, which are known at the time the award is made.

2. Comparison of the Two Approaches

As the plaintiff’s award is intended to replace an ongoing loss, it is important that the income the plaintiff receives from investment of that award is sufficient, in each period, to provide the desired compensation. In turn, this requires that the rate of return on that investment be as predictable as possible. The less predictable is the rate of return, the less certain can the courts be that the award will be sufficient for its purposes.

The predictability of the rates of return obtained under the annuity and active management approaches differs with respect to three characteristics: volatility of the rate of return on the invested funds, uncertainty concerning the plaintiff’s life expectancy, and protection against unanticipated increases in the rate of inflation. In this section, we compare the two investment approaches with respect to each of these characteristics in turn.

Volatility

The volatility of a class of investments refers to the variability in the rate of return earned on those investments over time. According to one source:

… volatility refers to the amount of uncertainty or risk about the size of changes in a security’s value. A higher volatility means that a security’s value can potentially be spread out over a larger range of values. This means that the price of the security can change dramatically over a short time period in either direction. A lower volatility means that a security’s value does not fluctuate dramatically, but changes in value at a steady pace over a period of time. [investopedia.com, emphasis added]

The more volatile is the price of a security, the more likely it is that the rate of return on that security will deviate from its long run average. In some periods the return will rise above the average and investors will experience a windfall; but in other periods, the return will fall below average and investors will experience a shortfall.

In the very long run, high returns and low returns may average out, and the rate of return obtained will trend towards the long run value. However, many plaintiffs do not invest for a period long enough that they can be confident that the rate of return on investment of their awards will settle on the long run average. This will particularly be true if plaintiffs are unlucky enough to make a major investment shortly before markets enter a sharp downturn such as was experienced in 2008, (or lucky enough to invest shortly before an upturn, such as in 2010).

To avoid the uncertainty that may result if the plaintiff’s award is invested in volatile financial instruments, it is often recommended that they concentrate their investments on secure, non-volatile stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. The Canadian courts have confirmed this recommendation. For example, in its seminal decision in Lewis v. Todd (1980 CarswellOnt 617), the Supreme Court of Canada approved of an expert witness’s use of “high grade investments [of] long duration.” [para. 17]

Investments in life annuities offer the lowest volatility possible: essentially, the rate of return is guaranteed as long as the insurer, and its re-insurers, remains viable.

Investments in an actively managed portfolio experience two forms of volatility that are not found with annuities. First, all but the most conservative, high grade investments experience variations in returns from year to year.

Second, even if a sophisticated investor could avoid most year-to-year variations in the rate of return, no investor can protect him- or herself against variations that occur due to long-term changes in the economy. For example, assume that it had been anticipated that the plaintiff would be able to obtain a two percent rate of return on investment of his/her award, because the economy was expected to grow at that rate. If broad economic fundamentals should change, such that long run growth fell to one percent per year, it is unlikely that the individual investor would be able to maintain a two percent return on investments.

To conclude, if the goal is to minimize volatility in the returns on the plaintiff’s investments, life annuities and structured settlements are superior to active management, especially in the long run. For short periods of time, perhaps five or ten years, an actively managed “portfolio of high grade investments” may offer almost as much security as an annuity.

Life Expectancy

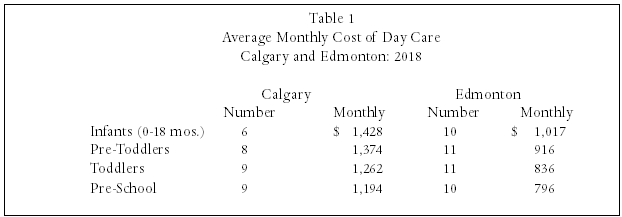

Assume that a plaintiff will require medical expenses of $50,000 per year for the rest of his life. In a personal injury action, his award will be calculated to ensure that if he invests that amount in a fund composed of secure investments, it will provide $50,000 per year for the lifetime of the average Canadian of his age and sex. For example, if he is a 50-year-old Canadian male his life expectancy is approximately 31 years, to age 81. Thus, his award will be calculated to ensure that he can remove $50,000 per year until his age 81, at which point the award have been drawn down (approximately) to zero.

This puts the plaintiff in a quandary: that the life expectancy of 50-year-old males is 31 years implies that (approximately) half of 50 year old males will live longer than 31 years (and half less than that). Thus, if the plaintiff spends $50,000 per year on medical expenses there is a 50 percent chance that his investment fund will be exhausted before he dies.

Alternatively, if he spends less than $50,000 per year, to leave money in the fund for the possibility that he will live beyond age 81, he will have insufficient funds in every year to pay for his required expenses. Even if it happens that the plaintiff lives less than 31 years, he will have been inadequately compensated for his necessary expenses, because he will have been taking the (reasonable) precaution of spending less than $50,000 per year to create a buffer for the possibility he will live longer than average.

In short, if plaintiffs invest their awards in actively managed investment funds, it is virtually certain that their awards will be insufficient to compensate them fully.

Furthermore, it can easily be shown that this outcome also arises when the amount to be replaced is a loss of income – although the shortfall will be less in this case than in the case of most medical expenses, because the impact of mortality is much lower when the loss continues only to retirement ages (when mortality rates are still low) than when it continues to the end of life.

If the plaintiff’s award is placed in a life annuity or structured settlement, however, payment of the desired annual compensation will be guaranteed from the date of settlement to the end date of the compensation period.

In short, whereas a life annuity will pay the plaintiff an amount equal to his or her loss in every year, an award invested in a portfolio of funds will, in most cases, undercompensate the plaintiff. This under-compensation will often be less when the award is intended to compensate for a loss of earned income than when it is to compensate for long term costs of care. Thus, on this ground, life annuities are slightly preferred to mixed portfolios of investments when there has been a loss of earnings; but annuities are definitely preferred when there is a long-term requirement for payment of medical expenses.

Unanticipated Inflation

A drawback to the annuity approach is that the stream of income that it provides may prove to be inadequate if inflation rates rise unexpectedly. For example, if an annuity provided for $10,000 per year, increasing each year at two percent (to allow for anticipated inflation), it would pay $12,190 in year ten. But if inflation proves to be four percent per year, the plaintiff will require $14,800 in year ten to buy what $10,000 would have bought in year one. The annuity will pay $12,190 when $14,800 is required.

It is often possible to buy annuities whose annual payouts increase with the actual rate of inflation. However, as the risk facing the sellers of annuities is quite high in this case, the price of these annuities may be higher than many buyers are willing to pay.

An alternative method of protecting against the effect of unanticipated inflation is to invest in an actively managed portfolio of assets. Under this approach, the individual is assumed to buy and sell financial assets on a continuing basis, replacing low-earning assets with higher-earning ones as market conditions change. If inflation increases, so will the returns on investments, particularly bonds, allowing the plaintiff to maintain a real rate of return (i.e. a rate net of inflation) that is consistent over time.

On this ground, if the rate of inflation cannot be predicted easily, the active management approach may be preferred to the annuity approach. However, central banks around the world have become convinced that one of their primary functions is to maintain a steady, low rate of inflation. The Bank of Canada, for example, has successfully targeted a rate of two percent since the early 1990s. This policy has been so well received that virtually all financial analysts expect this rate to be maintained well into the future.

As there is no reason to expect that the future rate of inflation will deviate significantly from the rate that has been experienced for the last twenty years, there is little reason to base the selection of the investment approach on the need to protect against unanticipated changes in the rate of inflation.

We conclude, therefore, that the ability of the active management approach to provide protection against unanticipated inflation does not offer a compelling reason to choose that approach in preference to the life annuity approach.

3. Summary

We summarise this section by investigating the merits of using the two investment approaches to replace (i) costs of medical care and (ii) losses of earnings.

Costs of Medical Care

For two reasons, if the plaintiff’s award is intended to provide compensation for medical expenses, particularly expenses that extend well into the future, we recommend that the award be invested in a life annuity (or structured settlement). First, as medical expenses are often required for the plaintiff’s entire life, it is important that the award is able to provide benefits should the plaintiff live beyond the average life expectancy. Whereas this can be achieved easily using a life annuity, it cannot be done through the active management approach.

Second, as the requirement for medical expenses often extends many decades into the future, the returns on awards invested in actively managed funds may be subjected to significant volatility, hence placing the risk of inadequate compensation on the plaintiff. The returns on a life annuity, however, are guaranteed by the insurer, thereby removing the risk of volatility from the plaintiff.

The contrary argument, for using the active management approach to the funding of future medical expenses, is that this approach allows for protection against unanticipated inflationary changes. We have argued, however, that such changes are not expected to be so large as to counter the arguments for use of life annuities. Furthermore, if the courts decide that inflation is likely to become an important factor, they can require that plaintiffs purchase inflation-protected life annuities.

We conclude that, in most cases, it should be assumed that when the plaintiff’s award is to provide for medical expenses, it will not be invested in actively managed funds but will, instead, be used to purchase life annuities. The exception occurs when medical expenses are required for only a short period of time.

Loss of Earnings

When the purpose of the plaintiff’s award is to replace a future stream of lost earnings, the argument in favour of life annuities is weaker than it was with respect to medical expenses. The reason for this is that earnings losses will generally end at an age at which the annual rate of mortality is still quite low.

For example, as we argued above, if a 50-year-old man has a life expectancy of 81, there is (approximately) a fifty percent chance that he will live beyond that age and will exhaust any award for medical expenses. Assume, however, that that individual had planned to retire at age 60, bringing any loss of earnings to an end at that age. As the probability of dying before age 60 is very small, the difference between an award that allowed for that probability and one that did not would also be small. Thus, any “error” that arose from using the active management approach might be compensated by other factors.

If we assume again that the risk of unexpected changes in inflation is small, then the primary difference between the annuity approach and the active management approach (with respect to losses of earnings) will arise with respect to volatility. On this basis alone, the annuity approach will be preferred as it offers less risk that an unanticipated fall in interest rates will leave the plaintiff’s award inadequate.

However, it is possible that this uncertainty concerning the rate of return on investments might be offset if the active management approach provided higher average rates of return. For example, if those rates were two or three percentage points higher than those offered by the sellers of life annuities, plaintiffs might prefer to manage their own funds rather than rely on an annuity.

For this reason, we suggest that the active management approach be employed only if it is clear that the plaintiff does not wish to invest his or her award in an annuity (as, in this case, the plaintiff has signaled that the rate of return on actively managed assets is high enough to compensate for the increased risk).

II. Evidence Concerning the Value of the Discount Rate

1. The Annuity Approach

If it is assumed that the plaintiff will purchase a life annuity, the appropriate discount rate will be the rate(s) of return that life insurance companies use when pricing those annuities. In this section, we argue that these rates will approximate the rates of interest that are available on Government of Canada bonds of the appropriate durations.

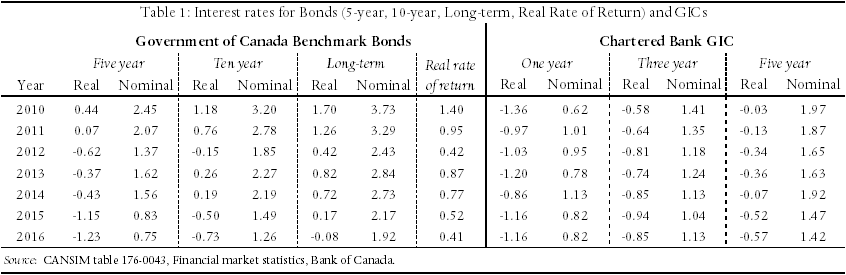

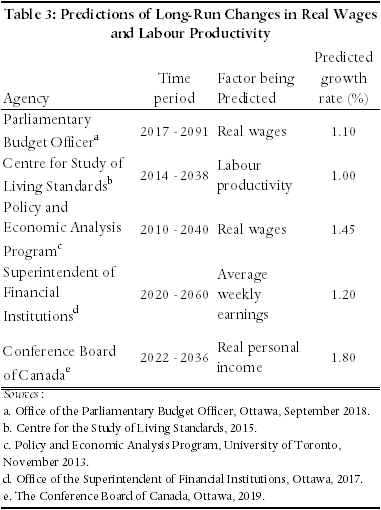

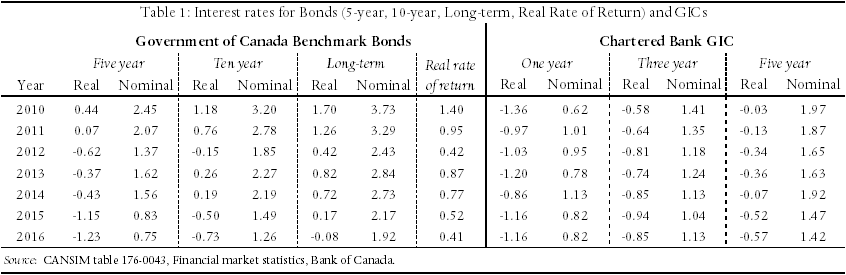

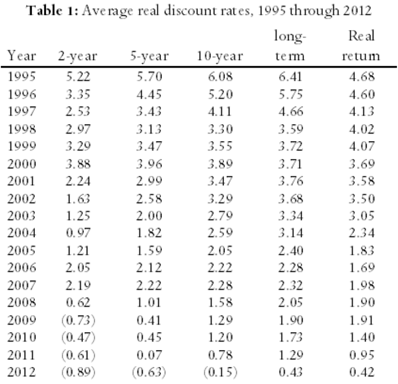

In Table 1, we summarise those rates for five-year, ten-year, long-term, and real rate of return bonds and for GICs of one-year, three-year, and five-year terms. In this table, the term “long-term bond” applies to government bonds with maturation dates of fifteen years or more. “Real rate of return bonds” are bonds whose rate of return is specified as a fixed value (the real rate of return) plus the actual rate of inflation. Thus, for example, if the fixed value is 1.0 percent and the rate of inflation proves to be 2.5 percent, the bond will pay (approximately) 3.5 percent.

Table 1 reports both the nominal (observed) and real (net of inflation) rates of return on five- and ten-year bonds, long-term bonds, and GICs. In each case, the real rate has been calculated by reducing the nominal rate by the expected rate of inflation, two percent. As the interest rate on real rate of return bonds is reported as a real rate, we report only the real rate of return on those bonds.

In Table 1 it can be seen, first, that the real rates of return on government bonds increase as the duration of those bonds increase; thus confirming that there is not a single discount rate but rather a different rate for each length of investment.

Second, it is also seen that the real interest rates on secure bonds have not recently risen above 0.5 percent for investments of any duration; and have risen above 0.0 percent only on real rate of return bonds.

Our contention is that these rates can be used as indicators of the rates at which life insurance companies will invest the funds they receive for life annuities and structured settlements. We can test this contention by comparing the interest rates employed to determine the prices of structured settlements against the rates reported in Table 1.

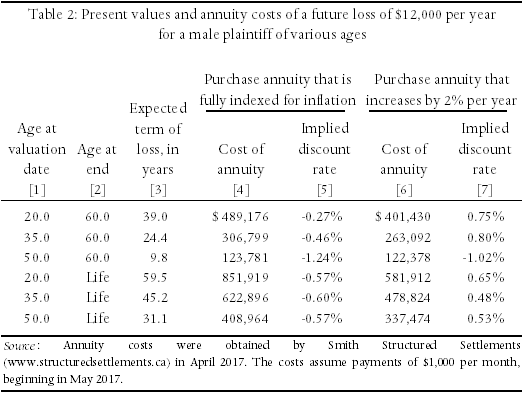

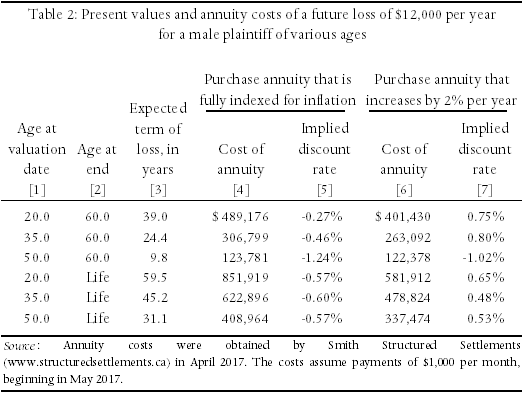

This we have done by obtaining quotes for several alternative structured settlements. From these we have been able to determine the interest rates that were employed to obtain those quotes. In Table 2 we report six such structured settlements, for males receiving $1,000 per month ($12,000 per year).

Three scenarios represent payments that end at age 60 and three represent payments that continue to the date of the plaintiff’s death. (Those that end at age 60 are assumed to be typical of awards for loss of earnings; and those that continue for life are assumed to be typical of awards for medical expenses.) The assumed ages for the plaintiffs, at the date of trial, are, respectively, 20, 35, and 60. Furthermore, in each case we report quotes for both the situation in which the annual payment is to increase by two percent per year and for that in which it will increase by the actual rate of inflation.

Column (4) of Table 2 reports the quotes we received, assuming that the annual payment was to increase by the actual rate of inflation; while column (6) reports the quotes assuming that the annual payment was to increase by two percent per year. Columns (5) and (7) then report our calculation of the implied interest rates that were used to obtain the costs of the various annuities.

For example, the first figure in column (4) indicates that it would cost $489,176 to purchase an annuity that paid a male plaintiff $12,000 per year, indexed for inflation, for the next 40 years (i.e. from age 20 to age 60). The first figure in column (5) then indicates that the insurance company that quoted this amount had implicitly assumed that its investments would earn an average real rate of interest, (i.e. nominal interest net of inflation), of -0.27 percent over the 40-year period in question. Similar costs and real interest rates are reported for the other eleven scenarios.

Notably, in every case in which the payments were fully indexed for future inflation (column 5), the implied real rate of interest was negative – between -1.24 percent and -0.27 percent. It is only when the payments did not provide full protection against inflation – column 7, in which increases were limited to two percent per year – that insurers offered a positive real interest rate. Even then, rates were less than one percent.

We would note that the implied discount rates of the annuities presented in Table 2 are consistent with the implied discount rates of annuities offered by private insurance firms such as Sun Life Financial and RBC Insurance. For example, the Sun Life Financial annuity calculator indicates that as of April 2017, a $1,000,000 annuity for a 50-year old female will provide an annual income of approximately $41,819 per year (with no inflation adjustment). This implies a discount rate of approximately 0.13 percent. The annuity calculator provided by RBC Insurance indicates that as of April 2017, a $1,000,000 annuity will provide a 55-year old male with annual payments of approximately $50,931 (with no inflation adjustment), for an implied discount rate of 0.15 percent.

It is informative to compare the rates employed in the calculation of structured settlements (and private annuities) with the rates reported for government bonds, in Table 1. The two annuities with the shortest durations – ten years, from age 50 to 60 – had implied discount rates of -1.24 and -1.02 percent, both very similar to the figure of -1.23 percent reported in Table 1 for five-year bonds in 2016. Similarly, the two annuities with the longest durations – from age 20 for life – had implied discount rates of -0.57 percent and +0.65 percent, with an average very close to the figure of -0.08 percent reported in Table 1 for long-term government bonds.

We conclude from Tables 1 and 2 that, in cases in which the plaintiff purchases a life annuity or structured settlement – particularly one that is fully indexed for inflation – the discount rate can be estimated with some accuracy from the real rates of return currently available on Government of Canada bonds of appropriate durations.

2. Active Management Approach

In the active management approach, it is assumed that plaintiffs will re-allocate funds within their investment portfolios as conditions in financial markets change. Because these changes will be made in the future, the active management approach requires that estimates of future rates of return be calculated.

In this section, we first identify the type of financial instrument in which we assume the plaintiff will invest. We then contrast two methods of forecasting the rates of return on those instruments. Finally, we provide estimates of those rates of return.

Selection of the Appropriate Financial Instrument

The courts have been clear that, as the lump-sum award is intended to replace the plaintiff’s lost earnings, the investments in the plaintiff’s portfolio must not expose the plaintiff to unreasonable risk. For example, in its seminal decision in Lewis v. Todd (1980 CarswellOnt 617), the Supreme Court of Canada approved of the expert’s use of “high grade investments [of] long duration” [para. 17].

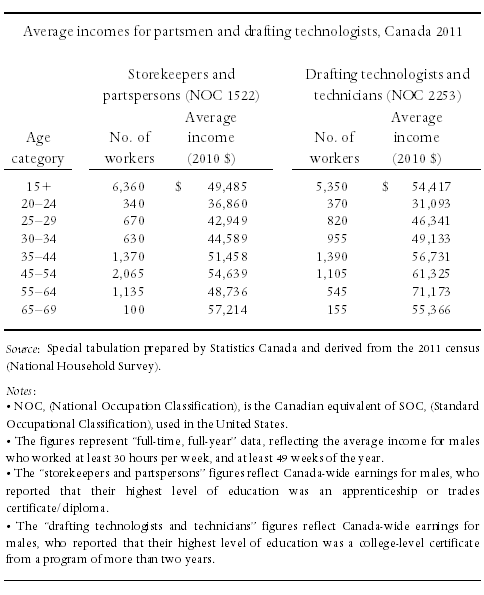

As the rates of return on investments in the stock market have historically been very volatile, it is usually recommended that plaintiffs do not restrict their investments to equities. Table 3, for example, reports the value of the Toronto Stock Exchange composite index for July of each year since 2000. It can be seen there that rates of return have been highly volatile, indicating that the rate available to an individual whose investments tracked the market would have depended importantly on the year in which those investments were made. For example, whereas the nominal return on investment in such a portfolio would have averaged 2.2 percent per year between 2000 and 2015, a similar investment would have averaged 6.2 percent per year between 2002 and 2015.

In light of this issue, two approaches might meet the court’s requirement that plaintiffs invest in high grade investments: it could be assumed that plaintiffs will purchase long-term Government of Canada bonds; or that they will invest their awards in financial instruments that offer higher yields than government bonds, but with greater risk – for example, in a mixed portfolio of “blue chip” stocks, corporate bonds, and mutual funds. In the discussion that follows, we will consider both.

Forecasting the Returns on Government Bonds

Two methods have commonly been used to forecast the rate of interest that will be available on government bonds. The first of these, the historical approach assumes that future rates will equal those that were observed in the past. The second, the efficient market approach, assumes that the rates that are currently available in the market reflect the rates that investors believe will prevail in the long run. We explain here why we prefer the efficient market approach.

The historical approach: A fundamental problem with the historical approach is that real interest rates have varied significantly over the last sixty years. As can be seen from Table 4, real rates were as low as 1.50 percent in two decades (1951-1960 and 1971-1980) and as high as 4.70 percent in two others (1981-2000). From this record, it would be possible to find support for almost any long-run rate between 2.0 and 5.0 percent.

More importantly, as indicated in Figure 1, real rates of return have declined virtually continuously for the past twenty years, from approximately 5.5 percent to -0.5 percent. Even if it was to be argued that real rates of interest will return to, say, 3.0 percent over the next twenty years, most plaintiffs will experience rates of return well below that over most of the period in which their award is invested.

A third problem with the use of historical rates is that there is no theory to support it. Adherents simply assume that because real rates took some value in the past, rates will return to that value in the future. Furthermore, they make this assumption in the face of the long run decline in real interest rates reported in Figure 1. If the markets expected the real rate of interest to return to “long-run” levels soon, sophisticated investors would not continue to purchase financial instruments that paid long-run rates as low as -0.08 percent (Table 1).

Finally, the evidence is not just that the real interest rate has declined significantly; this decline is consistent with theoretical predictions. Importantly, as central banks have adopted a policy of maintaining inflation within a narrow band of rates (in Canada, between 1.0 and 3.0 percent), uncertainty about the rate of inflation has been minimized. This reduction in risk has led to an increase in demand for bonds, and an associated reduction in real interest rates.

The Congressional Budget Office of the United States also predicts that interest rates will be lower in the future than in the past, resulting in part from slower growth rates of both the labour force and of productivity, thereby reducing the rate of return on capital; and in part from a shift of income to high-income households who tend to have high savings, thereby increasing the supply of money to the bond market.

The efficient market approach: The second source of information concerning future real rates of interest is the money market. When an investment firm that believes that inflation will average two percent per year purchases twenty-year Government of Canada bonds paying three percent, it is revealing that it expects the real rate of interest on those bonds will average approximately one percent over those twenty years. Thus, if the rate of inflation that investors were forecasting was known, that forecast could be used to deflate the nominal rates of interest observed in the market to obtain the implicit, underlying forecasts of real rates.

A strong case can be made for using an expected inflation rate of two percent. The reason for this is that in the last decade the Bank of Canada has not only made this its target rate of inflation, it has been successful in keeping the actual (long-run) rate of inflation very close to that target (which, in turn, has led most financial institutions to predict that future inflation will average two percent).

Furthermore, in choosing to target a low rate of inflation, the Bank has been following a view that has achieved widespread acceptance in the economics community – that is, that control of inflation, at a low level, should be one of central banks’ primary roles.

On this basis, at the end of 2016 the real rate of interest on long-term government of Canada bonds appeared to be as little as 0.00 percent. (See the figures for long-term bond rates in Table 1.)

An alternative approach is to rely on information concerning bonds whose rate of return is denominated in terms of real interest rates – called real return bonds, or RRBs. By observing the rates of return at which these bonds sell, the risk free real rate of return that investors believe will prevail over the long run can easily be determined. That is, even if plaintiffs do not purchase RRBs, the real rate of interest that is observed on those bonds provides an unbiased indicator of the rate of interest that is expected by sophisticated investors. In Table 1, it is seen that the return on these bonds has recently fallen to as little as 0.41 percent.

Forecasting Returns on a Mixed Portfolio

Forecasting the returns on a conservative, mixed portfolio is complicated by the fact that there is no common agreement about what the components of such a portfolio should be. Hence, not only is it difficult to obtain the current rates of return on conservative investments, there is also very little information about how such returns have varied over the past. Both issues complicate the forecasting process.

An approach that we suggest might mitigate this problem would be to rely on the rates of return that have been available on conservative portfolios offered by Canadian banks. We have been able to obtain information about four of these: the RBC Select Very Conservative Portfolio, CIBC Managed Income Portfolio, TD Comfort Conservative Income Portfolio, and ScotiaBank Selected Income Portfolio-Series A. Although these funds differ from one another in their details, they all have investment objectives similar to those stated for the RBC portfolio:

To provide income and the potential for modest capital growth by investing primarily in funds managed by RBC Global Asset Management, emphasizing mutual funds that invest in fixed-income securities with some exposure to mutual funds that invest in equity securities. The portfolio invests in a mix of Canadian, U.S. and international funds.

To achieve this goal, RBC invests primarily in bond funds. The result, seen in the first columns of Table 5 below, is that since 2011 this fund has consistently earned a nominal rate of return between 2.5 and 5.0 percent – with one deviation, to 6.74 percent, in 2014 – suggesting a real rate of return over that period of approximately 1.0 to 3.5 percent. Table 5 reports similar results for the other three portfolios (again, with 2014 being the only year that each of them achieved a nominal return that exceeded 5.00 percent).

The volatility in the rates of return on all four portfolios reported in Table 5 is considerably less than that on investments in the Toronto Stock Exchange, as reported in Table 3.

But that does not necessarily mean that plaintiffs would be advised to invest in a conservative mixed portfolio. Although the returns on such portfolios may be higher than that on life annuities, the returns on the latter are fixed once they are purchased, and hence have lower (zero) volatility than the returns on all other investments. The question remains: do the higher rates of return on mixed portfolios compensate the plaintiff for the higher volatility of their returns? This is a question that cannot be answered by financial experts, but only by the courts or government regulators.

What Table 5 does suggest, however, is that if plaintiffs had purchased mixed conservative portfolios in the last five years they would have achieved average nominal returns of between 3.5 and 4.5 percent per annum – or approximately 2.0 to 3.0 percent in real terms. This suggests that 2.5 percent represents a conservative estimate of the real rate available to plaintiffs seeking conservative investments.

III. Summary

In personal injury and fatal accident actions, the plaintiffs are assumed to invest their awards in such a way as to provide streams of returns that will replace their future annual losses. Two factors may intervene to hinder plaintiffs’ ability to achieve this goal. First, they may live longer than average. Second, the rate of return on investments may fall below the level that was anticipated when calculating their awards. In both cases, the award will be exhausted before the plaintiff’s death.

One approach plaintiffs can employ to avoid these problems is to invest their awards in life annuities or structured settlements, as these instruments guarantee a specified annual payment for life, and as the rates of return available on them are fixed.

The drawback to annuities is that the interest rates that insurance companies use to price their products are much lower than the rates of return that have been available on conservative mixed portfolios of financial assets. We showed in Section II that, whereas the implicit interest rates on life annuities are similar to the rates available on long-term Government of Canada bonds, or approximately 0.0 to 0.5 percent, the interest rates available on conservative portfolios of assets have been approximately 2.0 to 3.0 percent.

If a loss will not continue into the years beyond which mortality rates begin to rise substantially, the advantage of buying a life annuity may be relatively small compared to investing in a portfolio of assets. In that case, it may be appropriate to assume that that the discount rate can be estimated from the return on a portfolio of assets.

If the loss will continue into years of high mortality, however, the benefits of a life annuity (protection against exhaustion of the award) may exceed the costs (a lower rate of interest).

As it is only the plaintiff who can determine whether the benefits of a life annuity exceed the costs, it seems appropriate that the discount rate be chosen based on the plaintiff’s decision whether to self-manage the investment of his or her award or to use that award to purchase a life annuity (or structured settlement).

- If the plaintiff chooses to self-manage his or her award, we recommend that the discount rate be set at 2.5 percent.

- If the plaintiff chooses a life annuity or structured settlement, we recommend that the discount rate be set at zero percent.

- We anticipate that plaintiffs will make the latter choice in virtually all cases in which their losses will continue into years of high mortality.

Hanoun Multicervical Rehabilitation Unit (MCU) as an adjunct to traditional forms of assessment and rehabilitation. This leading edge, digital technology provides comprehensive objective and valuable cervical functional diagnostic data. It is used to effectively and objectively assess cervical range of motion and neck strength. Together, these measurements quantify the functional capacity of the neck. This differs from other functional capacity evaluations, in that this technology allows us to specifically measure the functional ability of the injured neck. Once functional deficits have been identified and diagnosed, the system can then be used to efficiently and accurately rehabilitate the injured area(s).

Hanoun Multicervical Rehabilitation Unit (MCU) as an adjunct to traditional forms of assessment and rehabilitation. This leading edge, digital technology provides comprehensive objective and valuable cervical functional diagnostic data. It is used to effectively and objectively assess cervical range of motion and neck strength. Together, these measurements quantify the functional capacity of the neck. This differs from other functional capacity evaluations, in that this technology allows us to specifically measure the functional ability of the injured neck. Once functional deficits have been identified and diagnosed, the system can then be used to efficiently and accurately rehabilitate the injured area(s).