by Derek Aldridge and Christopher J. Bruce

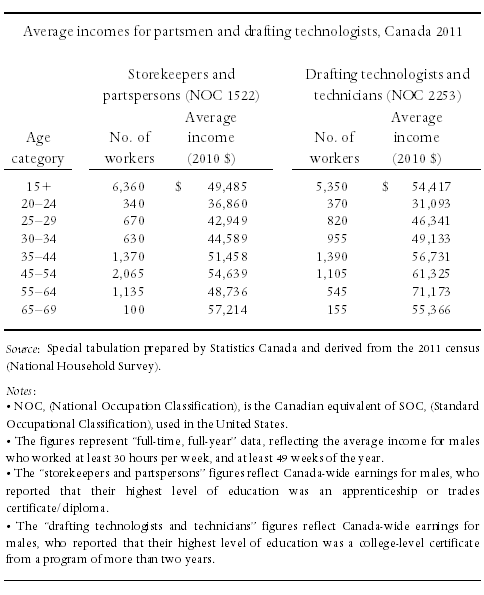

Vocational psychologists often recommend that injured plaintiffs retrain for a new occupation. An important question that arises in this situation is whether plaintiffs will start that occupation at an “entry-level” income (say the income of a 25 year-old) or at the income of an individual of the plaintiff’s calendar age. The importance of this issue can be seen in Table 1, which reports that, in two occupations that are commonly recommended as retraining possibilities – partsman and drafting technologist/technician – incomes for middle-aged workers can be 50 to 100 percent higher than those for 20-24 year-olds.

If it has been recommended that, say, a 40 year-old male retrain to enter one of these occupations, the economic expert is faced with determining which of the income levels from Table 1 best represents the income at which the plaintiff will begin his new career. If experience in the occupation, or movement along a career ladder, are important determinants of income, then we would expect that the plaintiff would begin at one of the lower incomes suggested by the census data. Perhaps with his greater maturity the 40 year-old would not start at the income level of a 20-25 year-old; but with no experience in this occupation, it seems unlikely that he would start at the income of a 40 year-old.

Fortunately, a number of empirical studies that provide information concerning this issue have been published in economics journals recently. We summarise the results of these studies here, to provide assistance both to vocational experts, who may not be familiar with the economics literature, and to economists, who may have been asked to calculate a loss in a case in which no vocational expert has provided a relevant opinion.

In the earliest of these studies, Goldsmith and Veum (2002) used a detailed survey that followed 1400 young workers from 1979 to 1996 to compare the effects of additional years of experience on wages when individuals: remained in the same occupation and industry, remained in the same occupation but moved between industries, remained in the same industry but changed occupations, and changed both occupations and industries. What they found was that the value that was placed on previous experience was approximately the same for all individuals except those that had changed both occupation and industry. In their words:

…experience acquired while a real estate agent is valued similarly as tenure at other occupations, such as accounting, within the real estate industry. In addition, the experience as a real estate agent is valued similarly to tenure at other industries, such as the pharmaceutical industry, if continuing in the occupation of sales. If the real estate agent becomes an accountant in the pharmaceutical industry, however, the experience as a real estate agent is of less value than that within accounting or the pharmaceutical industry.

(p. 442)

Referring to the examples in Table 1, Goldsmith and Veum’s findings suggest that the 40 year-old who retrains as a partsman may be able to earn an income comparable to that of a 40 year-old partsman with 15 years experience, if the retrained individual remains within his previous industry. For example, if an individual who had previously worked on oil rigs becomes a partsman in a shop that provides equipment to oil rigs, he might be expected to obtain a starting salary much higher than he would have obtained if he had become a partsman in an automobile dealership.

Subsequently, however, a number of studies cast doubt on Goldsmith and Veum’s findings. Both Zangelidis (2008), and Kambourov and Manovskii (2009) found evidence to suggest that occupation is much more important than industry. Zangelidis concluded, for example, that “[o]ccupational experience is expected to make an important contribution in determining wages…[whereas the] evidence on industry specificity… is not very supportive.” (p.439) And Kambourov and Manovskii (2009) concluded that “[job] tenure in an industry has a very small impact on wages once the effect of occupational experience is accounted for.”(p. 64)

The findings from these two studies suggest that if the plaintiff has not yet started a new post-accident job (and, hence, the wage at that job is not known), it may be appropriate to assume that she will begin that new job at an “entry-level” wage if she has re-trained for a new occupation (regardless of whether she remains in the same industry she was employed in before the accident); and will begin at a wage commensurate with others of her calendar age only if she has not changed occupations.

Hence, contrary to Goldsmith and Veum’s findings, these studies suggest that the 45-year old welder who retrains as a partsman will begin her new career at the earnings of a partsman at the start of her career.

Finally, two recent studies have asked whether the impact of retraining is a function of the worker’s initial occupation. For example: will craftsmen suffer a greater income loss if they are forced to change occupations than will salespeople? Sullivan (2010), using detailed information from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), found that changes of occupation and industry each had significant negative effects on the earnings of professional workers and clerical workers; that changes in occupation, but not industry, had negative effects on craftsmen and service workers; and that changes in industry, but not occupation, had negative effects on managers, salespeople, and laborers.

All of these studies imply that the reduction in earnings is likely to be greater, the greater is the difference between the tasks performed in the worker’s previous job and those in his or her new job – especially if the individual had initially been in a high-skill occupation, such as a professional or craftsman. As a first approximation, therefore, the empirical literature suggests using the earnings of individuals in entry-level jobs when estimating the starting income of an individual who has been forced to retrain, regardless of that individual’s calendar age. Of course, this recommendation will have to be modified when information specific to the plaintiff is found to be inconsistent with the statistical data presented here.

References

Gathmann, Christina, and Uta Schonberg.

“How General is Human Capital? A Task-Based Approach.” Journal of Labor Economics 28 (1) (2010) : 1-49.

Goldsmith, Arthur, and Jonathan Veum. “Wages and the Composition of Experience.” Southern Economic Journal 69(2), (2002): 429-443.

Kambourov, Gueorgui, and Iourii Manovskii. “Occupational Specificity of Human Capital.” International Economic Review 50 (1) (2009): 63-115.

Sullivan, Paul. “Empirical Evidence on Occupation and Industry Specific Human Capital.” Labor Economics 17 (2010): 567-580.

Zangelidis, Alexandros. “Occupational and Industry Specificity of Human Capital in the British Labour Market.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 55(4) (2008): 420-443

A version of this article was published in the Journal of Legal Economics, 24(1-2), September, 37-41.

![]()

Christopher Bruce is the President of Economica; he has a PhD in economics from the University of Cambridge

Derek Aldridge has been a consultant with Economica since 1995 and has a master of arts degree in economics from the University of Victoria.