by Christopher J. Bruce and Kelly A. Rathje

In fatal accident litigation, the plaintiffs are entitled to claim an amount that is sufficient to allow them to maintain the same standard of living as they had enjoyed when the deceased had been alive. In practice, this requires that the court calculate the percentage of the deceased’s after tax income that would have benefited the survivors directly. In Canada, this percentage is called the dependency rate.

Although most experts conclude that the dependency rate of one member of a couple is approximately 70 percent of the deceased spouse’s (after tax) income; there has recently been some confusion over whether the dependency rate might increase or decrease as family income increases. In particular, some experts have argued that the survivor’s dependency decreases as the deceased’s income increases. For example, whereas the widow of a man with low income might need, say, 80 percent of his income in order to be left in the same financial state as she would have had he lived, the widow of a wealthy man might need only 50 percent.

The purpose of this article is to employ a reliable source concerning after tax income, expenditure patterns, and savings – the Canadian Survey of Household Spending (SHS) – to investigate this claim. Based on the SHS, we show that the survivor’s dependency rate, in a husband/wife family, does not deviate significantly from 72 percent, regardless of the family’s level of income.

The article is divided into three sections. In the first, we argue that the Canadian data are reliable. Second, we calculate the dependency rate for a surviving wife at each of the five income quintiles. There we will show that that rate does not differ significantly from 72 percent at any of these quintiles. Finally, we comment on the treatment of savings in the calculation of the dependency rate.

We also include an Appendix in which we calculate a dependency rate by category for each of the 17 categories of expenditure in the SHS. [Note: in this article, we do not comment on the question of whether some portion of the survivor’s incomes – the portion they now “save” because they do not “have to” spend it on the deceased – should be set off against the survivor’s loss. The arguments we make here apply equally to both the set-off, or cross-dependency, and sole-dependency approaches.]

I. Survey of Household Spending

The most reliable source of family expenditure data in Canada is Statistics Canada’s Survey of Household Spending (SHS), in which approximately 15,000 families are interviewed. The most recent such survey (for which appropriate data are available) was conducted in 2008. The primary source of information concerning this survey is Statistics Canada’s Spending Patterns in Canada, 2008 (Catalogue No. 62-202-XWE).

The 2008 SHS breaks down gross family income into 18 components: 15 major categories on current expenditures, two categories that reflect future expenditure – “insurance and pension contributions” and “money flows” (where the latter is a measure of net savings) – and one for income taxes. Summary information is provided concerning: number of families in the sample, average family size, number of adults, children, and age of head.

Table 1 provides an example of the type of information that can be drawn from the 2008 SHS. The first column in this table reports the average annual expenditures on each of 17 categories (other than taxes). The second column reports the percentages of total (after tax) income that were devoted to each of these categories.

There are a number of reasons for believing that the SHS data are reliable. First, Statistics Canada makes an effort to collect information from the family head. Second, the data for recurring expenses, such as food and personal care, are collected using a detailed daily diary. Third, all other data are collected through personal interviews taking two to three hours. Finally, Statistics Canada has confirmed that the average incomes reported by respondents to the SHS are consistent with those collected from other sources (such as income tax data) 1.

II. Dependency Rates by Income Quintile

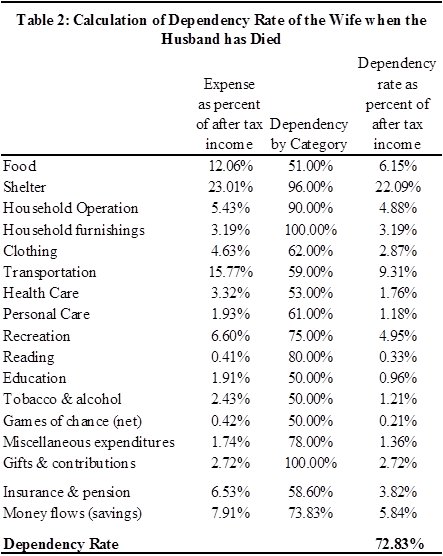

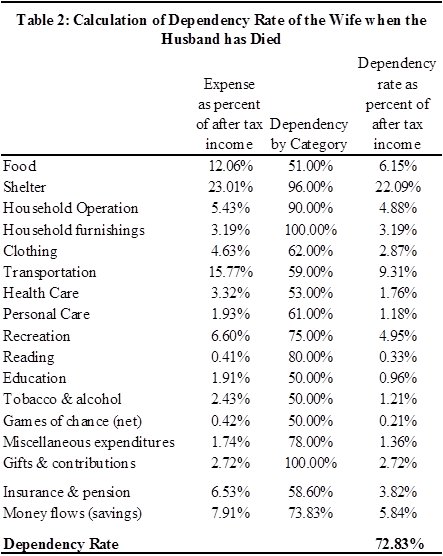

The Appendix to this paper calculates the dependency rate for each of the 17 categories reported in Table 1. This rate is the percentage of the pre-accident expenditures on that category that the surviving spouse will need in order to maintain his or her pre-accident standard of living.

These dependency rates are reported in the second column of Table 2. The rate for each category has been multiplied by the percentage of current consumption devoted to that category, taken from the first column of Table 1, in order to obtain the figures reported in the third column. The latter represent the percentages of pre-accident, after tax income that the surviving wife will need in order to maintain her pre-accident standard of living.

For example, the first row of Table 2 reports that the average Canadian family spent 12.06 percent of its after tax income on food, and that a widow will need 51 percent of this figure to maintain her pre-accident standard of living. Hence, she now needs 6.15 percent (= 0.51 × 12.06) of the family’s pre-accident income in order to purchase the food that she would have purchased had her husband not been killed.

When similar calculations are made for each of the 17 categories reported in Table 2, and the resulting figures are summed, it is found that the wife will require 72.83 percent of after tax income to maintain her pre-accident standard of living.

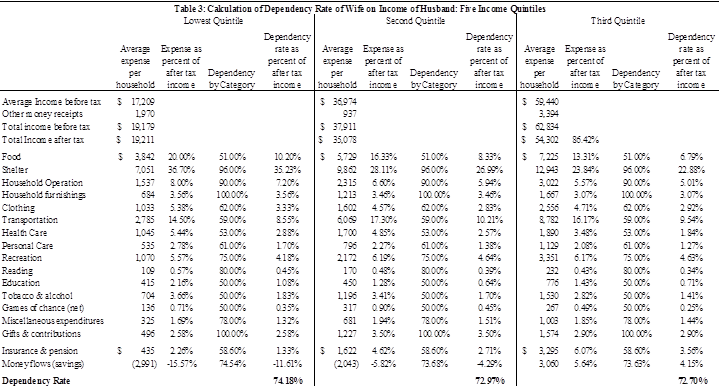

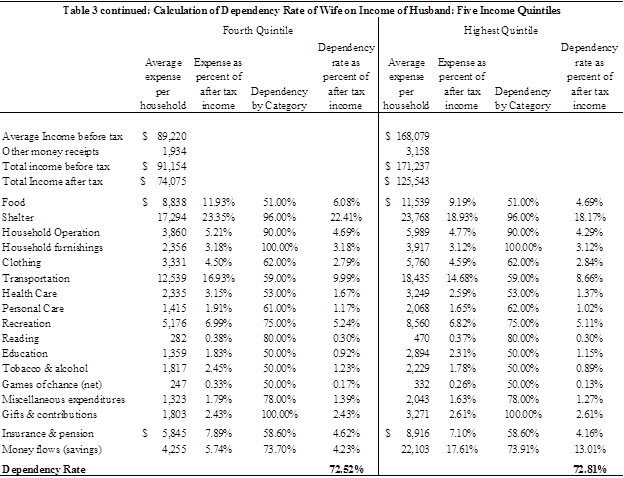

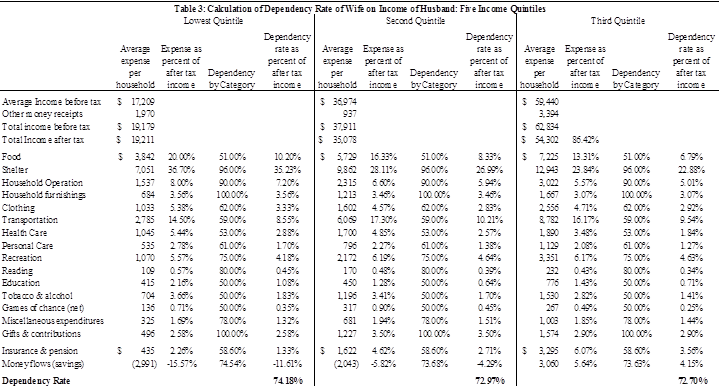

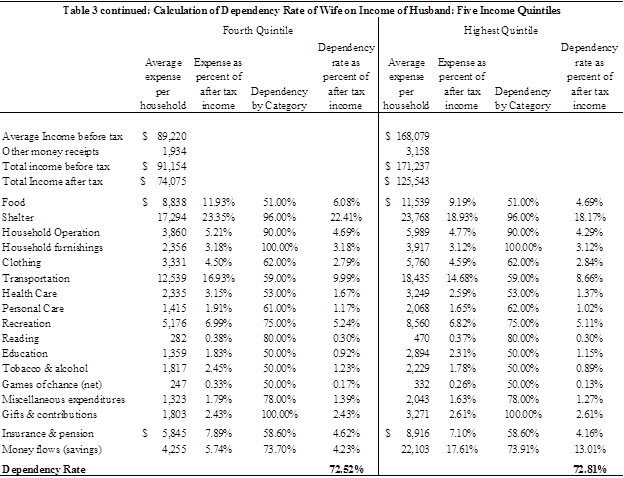

Using the same methodology employed to obtain the dependency rate for the average family, we also calculate dependency rates for families in each of the five income quintiles. In Table 3 (shown on the next two pages due to size constraints), we report the findings for each of these calculations, plus data concerning: the incomes of each of these groups and the distribution of their expenses among the 17 expenditure categories.

It is seen there that, before taxes, household incomes vary from a low of $19,179 for the first quintile to a high of $171,237 for the fifth; that income taxes range from 3.44 percent to 24.89 percent of total income; and that savings (as measured by the “money flow” category) range from minus 15.57 percent to plus 17.61 percent of after tax income.

The most compelling finding in Table 3 is that dependency rates do not vary significantly with gross income, with figures ranging from a low of 72.52 percent for the fourth quintile to a high of 74.18 percent for the first quintile 2. Although this finding may, at first, seem counterintuitive, three factors help to explain it.

First, it is seen in Table 3 that the distribution of expenditures among categories does not vary appreciably among income groups. For example, even in the category with the greatest difference among income groups, shelter, families in the fifth quintile spend only nine percentage points more than do families in the second quintile (28.11 percent versus 18.93 percent). In no other category does percentage expenditure decrease or increase by as much as seven points between the second and fifth quintiles.

Second, because the percentages of expenditures on the 17 categories have to add to 100 percent, every increase in the fraction of income spent on one category must be offset by a decrease in the fraction spent on another. Thus, as long as the dependency rates of the categories that increase are similar to those of the categories that decrease, the average dependency rate across categories will not change.

Finally, our finding that dependency rates do not vary significantly with income depends in part on the assumption that the survivor’s dependency on savings will be the same as her dependency on current consumption – that is, on the assumption that, to maintain her standard of living, the survivor will need the same percentage of the family’s retirement income as she needed of its current income.

If, however, the survivor could only be “made whole” if she was allocated a higher (or lower) percentage of retirement income than current income, then dependency rates would increase (or decrease) as income rose – because high income families devote a higher percentage of their incomes to savings. We discuss this issue in greater detail in Section III.

III. Dependency on Savings

Assume that a husband and wife have family income of $80,000 per year, after taxes, of which they devote $70,000 to current expenditures (that is, to expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, etc.) and $10,000 to savings. Assume also that the wife’s dependency on current expenditures is 70 percent – that is, that she benefits from $49,000 (= 0.70 × $70,000) worth of goods and services each year (during the years in which her husband is working). If her husband is killed, she will require replacement of that $49,000 if her standard of living is to be maintained.

In addition, her husband’s death will deprive her of the benefit she would have received from the (ultimate) expenditure of the $10,000 per year that the couple was saving. In Section II, we assumed that the couple would have spent that money in a manner that was similar to the way in which they were spending their income on current expenditures. Therefore, we would have applied a dependency rate of 70 percent to the $10,000 to determine the loss to the wife.

It appears to us that there are two arguments against use of the latter assumption. First, it may be that, as retired couples have lower incomes than working-age couples, their expenditure patterns will also differ, resulting in different dependency rates. However, as we have found that dependency rates do not vary significantly across income levels (see Section II), this argument is not likely to have a significant effect on the results in Table 3.

Second, it is possible that couples may intend to leave a large portion of their savings either to charity or to their children.

To the extent that charitable donations and bequests are a “public good,” the surviving spouse may need as much as 100 percent of planned donations if she is to maintain her standard of living. For example, if the couple had planned to give $100,000 to their daughter, the surviving wife will not be left “equally well off” if the death of her husband leaves her able to give some amount less than $100,0003.

Assume, for example, that within the highest quintile, couples plan to spend 60 percent of their savings on the purchase of goods and services (when retired), and 40 percent on donations and bequests. If it is assumed that the wife’s dependency on current expenditures is 70 percent and her “dependency” on donations and bequests is 100 percent, her total dependency on savings will be 82 percent (= 0.60 × 70% + 0.40 × 100%), instead of the 73.91 percent we applied to savings in Table 3. In that case, however, her total dependency on after-tax income would increase by less than 1.5 percentage points.

Furthermore, this argument has almost no effect on the dependency rates for couples in the first four quintiles as their savings rates are either very low or negative (implying very small donations and bequests). Thus, once again, adjustment of the assumption concerning dependency on savings has no significant effect on the general conclusion that dependency rates do not vary appreciably with income.

APPENDIX: Dependency Rate by Expenditure Category

The purpose of this Appendix is to calculate the dependency rates for each of the seventeen expenditure categories identified in the Survey of Household Spending.

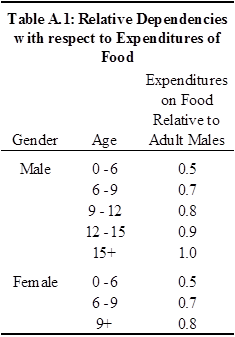

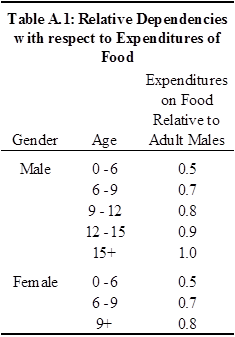

a) Food: Two steps must be taken in order to determine the dependency with respect to expenditures on food. First, it is necessary to identify the relative consumption levels among family members of different ages and sex. Second, allowance must be made for the fact that economies of scale from bulk buying are lost when one member is removed from the family.

With respect to the first of these calculations, our research indicates that the relative consumption of food, among family members of different ages, can be approximated by the figures in our Table A.1.

For example, if a family is composed of a husband and wife, for every 1.0 “units” of food consumed by the husband, the wife consumes 0.8 units. In this case, the couple consumed 1.8 units of food, of which 44.4 percent (0.8 ÷ 1.8) was devoted to the wife. It is this figure that has been used in the construction of Table 2.

Based on the above, and on the general finding that food costs approximately 10 percent more for a single person than for each member of a married couple due to loss of economies of scale, we conclude that in a family of two adults the dependency would be 51 percent when it is the husband who has died and 61 percent when it is the wife. In a family of four, the dependency would be approximately 76 percent if the husband should die and 83 percent if the wife should die.

b) Shelter: The shelter category consists primarily of payments for rent, mortgage, repairs and maintenance, and utilities, none of which could be expected to be reduced appreciably following the death of a spouse. For this reason, we recommend that the dependency be set at 96 percent. This is the figure that has been entered the second row of Table 2.

c) Household operation: This category consists, principally, of expenses for telephone, child care, domestic services, pet care, household cleaning supplies, paper supplies (e.g., toilet paper and garbage bags), and gardening supplies. Of these, only expenses on telephone and paper products can be expected to vary appreciably with family size. Accordingly, we set the dependency rate at 90 percent for the childless family.

d) Household furnishings: As there is no element of this category on which expenditures would be reduced by the death of a spouse, the dependency is 100 percent.

e) Clothing: The most reliable source of data concerning the division of clothing expenditures among family members is Statistics Canada’s Family Expenditure Survey, 1986. Relying upon that source, we have calculated that a family of two adults and two children (aged five to nine) would require approximately 0.6 adult male units for the boy’s clothing, 0.8 for the girl’s clothing, 1.65 for the wife’s clothing, and 1.00 for the husband’s. Thus, the dependency would be approximately (3.03 ÷ 4.05 =) 75 percent if the husband should die and (2.40 ÷ 4.05 =) 59 percent if the wife should die. In a family of two adults, the equivalent dependencies would be 62 and 38 percent, respectively.

f) Transportation: Approximately 90 percent of transportation is devoted to the purchase, maintenance, and operation of cars and trucks. Thus, the most important determinant of the dependency in this respect will be the number of vehicles owned by the family. If both adults drive but own only one car, the death of one of them can be expected to have little effect on vehicle costs; that is, the dependency would be relatively high. However, if the family owned more than one vehicle, including one that was used primarily by the deceased, the dependency may be as low as 50 or 60 percent.

For the purposes of illustration, we have assumed in the construction of Table 2 that the family had two cars, giving it a dependency with respect to vehicles of approximately 60 percent. The remaining 10 percent of the transportation budget is devoted to public transportation (including air fares).

Assuming that these expenditures are divided evenly among family members, the total dependency with respect to transportation is 62 percent (= [0.9 × 0.6] + [0.1 × 0.75]) for a four-person family and 59 percent (= [0.9 × 0.6] + [0.1 × 0.50]) for a two person family.

g) Health care: Approximately 30 percent of this expenditure is devoted to health insurance. As premiums generally do not double when family size is increased from one to two, we assume for purposes of illustration that the dependency with respect to health insurance premiums is 60 percent for a two-person family. The remaining 70 percent of the average family’s medical budget is devoted primarily to eye care, dental care, and drug purchases. Lacking any firm data on the distribution of these expenses within the family we shall, for purposes of illustration, assume that they are divided equally. Thus dependency for a two-person family is 53 percent (= [0.30 × 0.6] + [0.70 × 0.5]).

h) Personal care: Personal care includes expenditures on such items as haircuts, hair and makeup preparations, soaps, deodorants, and shaving preparations. The recommended budget developed by the Social Planning Council of Toronto shows that adult females spend approximately 63 percent more than adult males on these expenditures. Hence, if it is the husband who has died, the wife’s dependency is approximately 61 percent.

i) Recreation: Approximately 50 percent of the average family’s recreation budget is devoted to expenditures that may not vary with the size of the family, such as purchases of recreational vehicles and home entertainment equipment. The remaining 50 percent is devoted to admissions to events, purchases of home recreational equipment (such as games and crafts), and purchases of sport and athletic equipment. Assuming that the latter expenses are shared equally among family members, the dependency with respect to recreation proves to be 75 percent (= [0.5 × 1.0] + [0.5 × 0.5]) for a two-person family.

j) Reading: The approximate division of reading is: 35 percent on newspapers, 20 percent on magazines, and 45 percent on books. Assuming that newspaper expenses do not vary by size of family and that one-third of book and magazine purchases are specific to one of the adult members of the family, the dependency with respect to reading proves to be approximately 80 percent (= [0.35 × 1.0] + [0.65 × 0.67]).

k) Education: In the absence of any information concerning the plaintiff family, and recognizing that less than 20 percent of the education expenses listed by Statistics Canada are devoted specifically to young children, the only assumption that can be made with respect to this category is that expenses are divided equally between the two adults if there are no older children in the family. That is, for purposes of Table 2, the dependency is 50 percent.

l) Tobacco and alcohol: As with education, in the absence of specific information about the family and assuming that there are no older children in the family, the dependency for tobacco and alcohol must be set at 50 percent.

m) Games of chance: In the absence of other information, we assume that the couple divides these expenditures equally. That is, the dependency rate with respect to this category is 50 percent.

n) Miscellaneous: Of the expenses listed under Miscellaneous, approximately 70 percent reflect items that would not vary significantly with family size, such as interest on personal loans, purchases of lottery tickets, bank charges, lawyers’ fees, and funeral expenses. Assuming that the dependency with respect to these items is 90 percent and with respect to the remaining items is 50 percent, the total dependency with respect to the miscellaneous category is 78 percent (= [0.7 × 0.9] + [0.3 × 0.5]).

o) Personal insurance payments and pension contributions: Approximately 70 percent of the expenditures in this category are for pension fund payments (primarily the mandatory, government-operated Canada Pension Plan), 15 percent for life insurance premiums, and 15 percent for employment insurance premiums. Thus, the value of the dependency will be determined primarily by the labour force attachments of the adult members of the family and by the number and ages of children.

Consider, first, the life insurance premiums. In a two-adult family, life insurance is normally taken out on the life of the main income earner, with the second family member being the beneficiary. If either family member dies, the need for such insurance is reduced significantly. That is, the dependency is (approximately) zero.

In a family with children, however, it may be the children who are made the beneficiaries. Therefore, regardless of which parent has died, the remaining parent can be expected to continue his or her payments to a life insurance scheme. Indeed, that parent may even increase life insurance coverage to take account of the fact that a further death would leave the children with no parents. In such a case, a 100 percent dependency would appear reasonable.

The value of the dependency with respect to employment insurance contributions will be determined by the employment status of the adult members of the family. If the deceased was employed and the survivor is not, no contributions will now have to be made to employment insurance. Therefore, the dependency is zero. On the other hand, if the deceased was not employed and the survivor is, contributions will be unaffected. That is, the dependency is 100 percent. And if both adults were fully employed, the dependency will be 50 percent.

Finally, when the family loses the deceased’s contributions to a pension plan, it loses the future consumption it would have enjoyed from that pension. As it is only the spouse, and not the children, who would have benefited from this pension, it is the surviving spouse’s dependency on the couple’s retirement level income that will be relevant.

Applying the technique described in Section II, above, we find that if both members of a couple are over 65, the surviving spouse will have a dependency rate of approximately 73 percent (whether it is the wife or the husband that has died). Hence, if both spouses had been fully employed, the total dependency on the personal insurance and pension contributions category becomes 73.6 percent (= [0.15 × 1.0] + [0.15 × 0.5] + [0.70 × 0.73]) when there are children and 58.6 percent (= [0.15 × 0] + [0.15 × 0.5] + [0.70 × 0.73]) when there are not.

p) Gifts of money and contributions: This category consists of gifts to individuals outside of the family-spending unit – for example to parents and children living in separate households – and of charitable donations. We believe it can be argued that if the wellbeing of the survivors is to be maintained at the pre-accident level, these contributions must also be maintained at the pre-accident level. That is, the dependency with respect to this category is 100 percent.

q) Money flows – assets, loans and other debts: The purpose of this category is to measure households’ net contributions to (or withdrawals from) savings. Its primary components are changes in bank balances, purchases of stocks and bonds, contributions to registered retirement savings plans, and changes in money owed by (or to) the household. To the extent that any money put in to savings will be spent later, the dependency on this category will be the same as the dependency on expenditures that were made while the family members were working, or approximately 74 percent, (see Section II). However, if a significant portion of the household’s financial assets are passed to the couple’s children, through their estate, the dependency on savings approaches 100 percent (as for “gifts and contributions”). For the purposes of the sample calculations reported in Section II, we have assumed that the couple spends all of their savings during their lifetimes. Accordingly, we employ a dependency rate equal to the dependency on current consumption, or approximately 74 percent.

Footnotes:

- Personal interview with Danielle Zietsma, Senior Economist, Survey of Household Spending, Statistics Canada, May 31, 2013. [back to text of article]

- We repeated the exercise in Table 3 using data for the situation in which it is the wife that had died. The dependency rates for the five quintiles did not change appreciably. They became 74.07%, 72.63%, 71.95%, 71.57%, and 71.56%, from lowest to highest quintile.[back to text of article]

- In Ratansi v. Abery (1994), 97 B.C.L.R. (2d) 74 (S.C.) the deceased parents had contributed a substantial portion of their income to their mosque. The court found that it was not “….appropriate or accurate to describe the monies contributed to that institution as ‘income not available for family expenditure’.” Accordingly, the dependency of the surviving children on this portion of their parents’ income was found to be 100 percent.[back to text of article]

Christopher Bruce is the President of Economica and a Professor of Economics at the University of Calgary. He is also the author of Assessment of Personal Injury Damages (Butterworths, 2004).

Kelly Rathje is a consultant with Economica and has a Master of Arts degree (in economics) from the University of Calgary.