Derek Aldridge, Economica

derek@economica.ca

(I consent to redistribution of this unmodified document)

ACTLA Presentation – Lunch and Learn

March 25, 2021

Loss of income for self-employed plaintiffs

I will briefly discuss the approach that I use to estimate the loss of income for self-employed plaintiffs. Simply determining the true income of a self-employed worker can be challenging, and I will address some of these challenges. I will also discuss some approaches that can be used to estimate their loss of income.

Note that my tables and charts are based on actual cases I have worked on, but I have made various adjustments to simplify the presentation to preserve confidentiality.

Estimating the income of a self-employed worker

Determining the income of a self-employed worker can be much more complicated than for a regular employee.

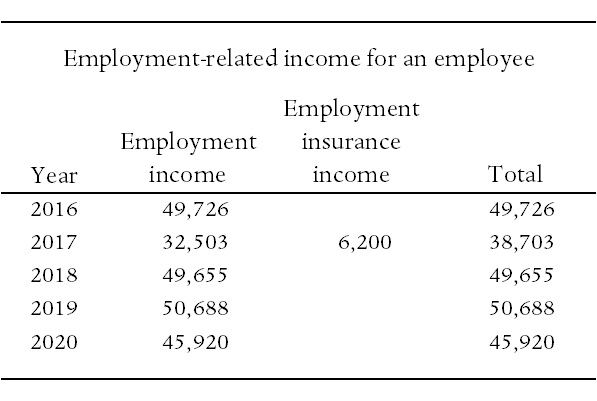

For a plaintiff who is an employee and not self-employed, their income is simply the amount they are paid by their employer. Employment insurance income is also relevant for our calculations. Both of these sources of income are usually easy to determine by looking at the plaintiff’s income tax records. An employee might have income tax records that look something like this:

Usually, the income tax records will give us an accurate description of the income of an employee-plaintiff – at least for the pre- accident period. After the accident there can be income replacement benefits that do not appear in the income tax records.

For a self-employed worker, their personal income tax records usually only tell us part of the story of their income. The personal income tax records for a self-employed plaintiff might look something like this:

For the self-employed worker, the income reported on their personal tax returns will often not reflect their true income in each year. I will discuss this below.

For my purposes, there are two categories of self-employed workers: those who operate their business as a sole proprietorship, and those who operate a corporation.

Sole proprietorship

- These are usually fairly straightforward.

- All business income appears on the personal income tax returns – usually as gross and net business income.

- There is a statement of earnings with the personal tax return that shows a detailed description of revenue and expenses.

- All business income is paid to the business owner each year. There is no separate corporation where profit can be held separately from the owner. Because there is not a separate corporation, most of the information we need to estimate the plaintiff’s income is usually contained in their personal tax records.

Corporation

- These are more complicated, and I will focus my discussion on cases when the plaintiff’s business is a corporation.

- The plaintiff operates his business through a numbered or named corporation (for example, 1234567 Alberta Ltd, or Derek Aldridge Consulting Ltd). The corporation is a separate entity from the plaintiff, so income earned through the corporation will not necessarily appear on the plaintiff’s personal income tax records. That is why we need the corporate financial statements.

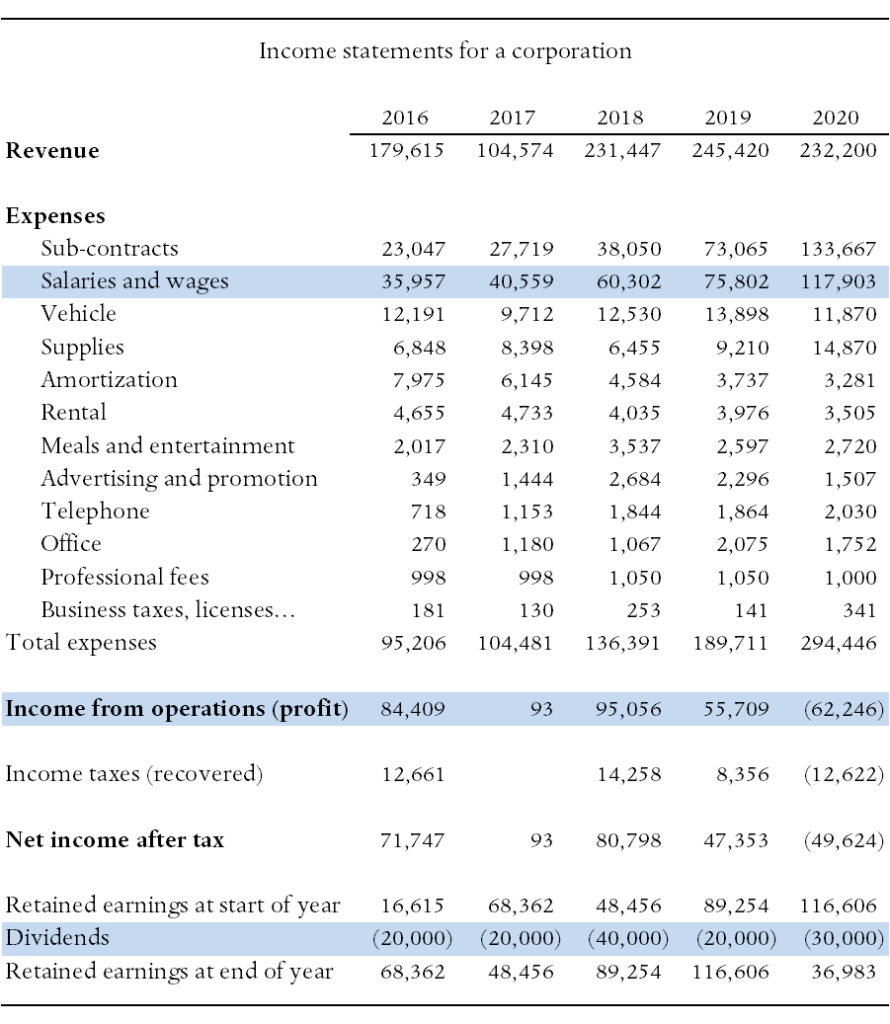

- The business income statements show the revenue and expenses for each year. When I combine the income statements for several years, I create a table that looks something like this:

The income statements can get quite complicated, but in general, we see the revenue at the top, which is the income the business earned each year. Then we have various categories of expenses. The business owner usually pays himself a salary, and it is included here as an expense, because his salary is an expense to the business. The salary for other workers at the business is also likely included in that same expense category. The revenue less the expenses gives us the income from operations (profit), before accounting for corporate taxes. In principle, the business owner could pay himself a high enough salary so zero profit would remain. But usually what happens is some of the profit is left in the business as retained earnings, which is effectively savings (the corporation does not need to pay out all profit to the owner every year). The business financial records will show us how these retained earnings have accumulated over time, and will also show us when the owner draws down these savings by taking dividends.

When examining the corporate income statements, I am most interested in how much the business paid the owner in salary (part of the business expenses), and how much before-tax profit the business had after expenses, since that profit effectively belongs to the owner and could have been paid to him as part of his salary. The business owner’s income is the total of the salary (employment income) that the business paid him, plus the profit that the business earned. The salary is reported on his personal tax return, but the business profit is not. The owner might also report dividend income from the corporation, but I do not normally count this as part of his income. Because I am attributing all of the business profit to the owner in each year, this captures all of the dividend income that could be paid in future years.

Note that dividend income can cause some confusion because it does not necessarily reflect earnings from the year under consideration. If the business has accumulated significant retained earnings from previous years’ profits, the owner could still pay himself a large dividend in a year when business was poor.

Below I compare the income reported on this business owner’s personal income tax records with his true income:

We see that there can be quite a large difference between the business owner’s true income and the income that is reported on his personal income tax records. Another potential complication is that the corporation reports its income in a fiscal year, which may be different from a normal calendar year. So if fiscal 2019 for the corporation is the 12-month period from August 2018 through July 2019, it will make it more difficult to match up income reported on the personal tax returns with the corporate financial statements.

Documents and information required

Below I list some of the documents and information that I like to have when dealing with a self-employed plaintiff.

- The business income statements show the revenue and expenses for each year.

- The balance sheet is usually included with the income statement as part of the annual financial statements that are usually prepared by an accountant. However, there is usually not much useful for me in the balance sheet.

- I need the plaintiff’s personal income tax records because they will show the salary (employment income) that he drew from the business.

- Sometimes the business pays a salary to another family member. Perhaps the owner’s wife does bookkeeping and the business pays her a salary of $20,000 per year. That’s fine, but if she is being overpaid for this work (income-splitting) then I should account for this. For example, if she is being paid $20,000 but an arms-length bookkeeper would only be paid $12,000, then that extra $8,000 actually reflects the plaintiff’s income.

Approaches to determine a loss of income

Once we have a good estimate of the plaintiff’s true income in every year, the next step is to try to estimate his loss of income in each past year, and in the future. While I am focusing on cases when the plaintiff owns and operates a corporation, many of the same principles apply for sole-proprietorship cases.

One of the first things to consider is what is being claimed was the impact of the accident on the business income? This might look obvious from the financial records (for example, a sharp decline in revenue in the years following the accident), but there could be many other effects.

If business revenue declined following the accident, why was that? Is it because the plaintiff missed a few months of work? Is it because she reduced her work hours? Is it because she was less productive during the hours that she worked? Did she target jobs that were less physically demanding and less lucrative? Did she miss out on certain high-value contracts? In my view, answering these questions can be an important part of the narrative. There can be many reasons for a decline in revenue that are unrelated to an injury, so we want to know what is the reason for the revenue decline that we have observed.

Note that it could be the case that business revenue did not decline, but if the accident had not occurred, revenue would have been higher. That is, revenue might have been stable or increasing after the accident, but still less than it would have been absent the accident.

Sometimes business expenses increase because of the accident. This could happen if a worker or a subcontractor was hired to take on some of the duties that the plaintiff normally would have performed. This should also be accounted for in my calculations.

In some cases we can simply compare the plaintiff’s total business income in the years before the accident with her income after, and estimate a loss on that basis. However, because of the many factors that can influence business income, it is often preferrable to try to account for the specific impacts that the plaintiff’s injures had on her business revenue and expenses.

In one case, I had a self-employed worker who had a fairly straightforward business and she billed her services to several clients at an hourly rate. The claim was that because of her injuries, she was reduced in her ability to work and bill hours. Billing more hours would not have led to significant increased expenses. Fortunately, she had detailed records showing her billing and the pattern confirmed her claim:

As shown above, it appears that this plaintiff’s billed hours declined greatly following the accident. They have improved somewhat, but she continues to bill less than she did before the accident.

In this case I was able to estimate a loss of income by assuming that if the accident had not occurred, the plaintiff would have continued to bill her average monthly hours from before the accident, whereas with-accident, she will continue with her reduced billable hours. For the future calculations I can also include scenarios in which I assume that her billable hours will decline further (her condition declines), or that her billable hours will increase (her condition improves).

By examining the billable hours (instead of billings), this helps us account for revenue increases that are due to increases in the plaintiff’s hourly rate, versus increases due to billing more hours. For example, if the plaintiff has increased her hourly rate by 20 percent in the years following the accident, this could easily mask the revenue-effect of her average monthly hours having declined by 20 percent.

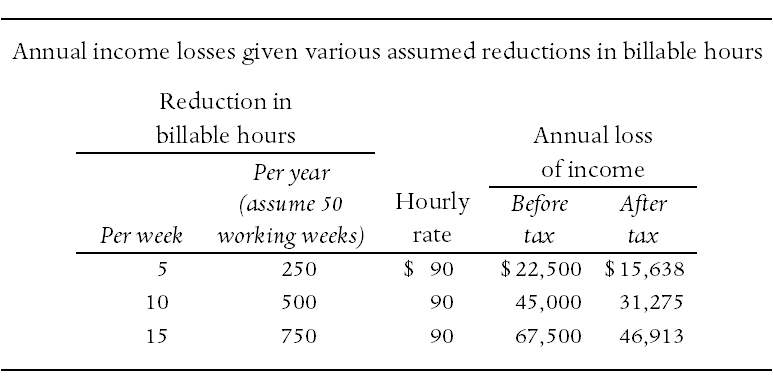

In another case that I worked on, the plaintiff was self-employed in a personal-services business and she charged an hourly rate for her services. It appeared that her total billable hours had decreased due to her injuries, and my client wanted me to simply provide a range of scenarios regarding the loss of income that would result from various reductions in billable hours. In the table below I show the potential annual loss that resulted from assumptions that her billable hours have been reduced by 5, 10, or 15 per week.

A case in which a plaintiff bills her services hourly, has no employees, and expenses that are mostly fixed (not increasing with additional billable hours), is almost an ideal scenario for estimating the loss. Her loss of income is directly linked to her ability to bill hours. Other cases can be much more complicated.

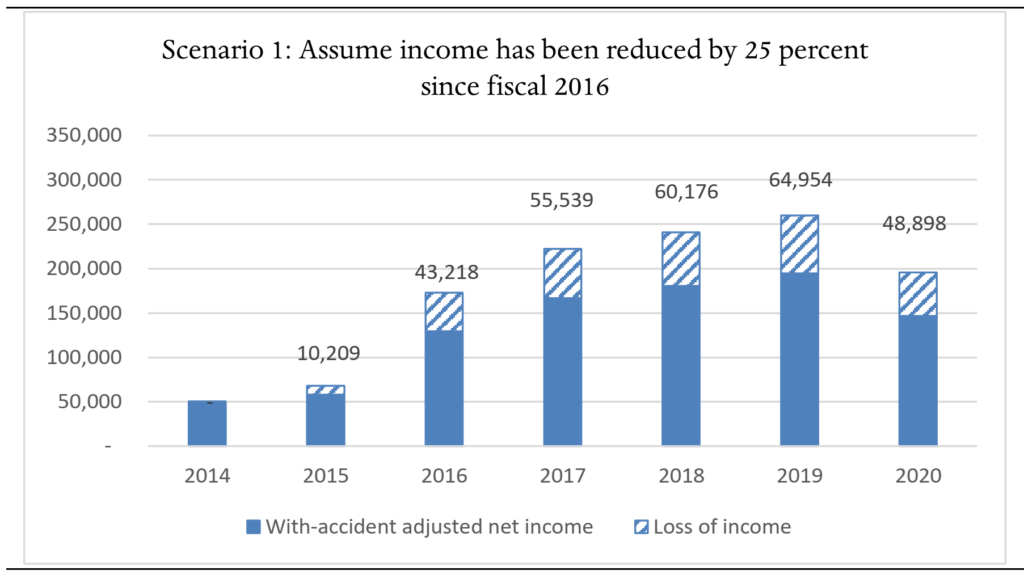

Another case that I worked on involved a plaintiff who was in the early stages of establishing his business when he was injured. Following the accident he was able to continue to grow his business, and his income increased accordingly. His business income was fairly complicated, with employees who also generated revenue, as well as numerous expenses. After estimating the income that he earned from his business, the potential loss of income was not at all obvious because his income had increased so much after the injury, as shown below.

Because the plaintiff was injured while he was in the early stages of establishing his business, I didn’t have a useful pre-accident history as a comparison. However, his business income was heavily linked to his ability to spend time at work, and to be productive during that time. Because of his injuries, it was claimed that he needed more many breaks at work and he was not able to perform some of the more lucrative jobs that would normally have been available to him. Effectively, the evidence was suggesting that if he was uninjured, his revenue and earnings would be much greater. The question of course, is how much greater? Ultimately I provided a range of scenarios, and one was that I assumed that his income has been reduced by 25 percent because of his residual deficits. (That is, he has only been earning 75 percent as much as he would have been earning if uninjured.) This is depicted in the chart below.

Clearly this is not as exact as we might hope, but providing a range of scenarios using this approach can at least provide an estimate of the loss if the Court accepts a certain set of assumptions. Dealing with a self-employed plaintiff can involve much more uncertainty than when we have (say) a teacher who is working three-quarters of full-time because of her injuries, rather than full-time.

Another approach that can potentially be useful is the replacement cost approach. In some cases it is possible for the plaintiff to hire a helper that will enable the business to continue as it would have in the absence of the accident, though with additional expenses (and reduced profit) due to the cost of the replacement worker. For example, an injured owner of a landscaping business might be able to hire a part-time labourer to assist him with some of the heavier tasks. If this helper is paid $40,000 per year, then business expenses will increase by $40,000 and profit will decrease by $40,000. That’s $40,000 that is not available to be paid to the owner, so his annual loss of income due to hiring the replacement worker would be $40,000 (not accounting for tax). In this case I am assuming that the self-employed landscaper can continue with the managerial aspects of his business, and he can perform some of the manual labour, but his residual deficits are preventing him from performing the heavier tasks.

The possibility of hiring a replacement worker is something that should especially be considered when the plaintiff is claiming that his income loss is particularly high. If the self-employed landscaper in my example above is claiming a huge annual loss, it is reasonable to ask why his loss is not capped at around the cost of a full-time labourer. But in other cases, the cost of hiring an assistant is not going to be a reasonable approach. For example, a surgeon with a back injury presumably cannot mitigate her losses by hiring a helper – her best option might be to take longer breaks in between procedures.

* * *

For a PDF version of this presentation, click here.