by Christopher J. Bruce, Kelly A. Rathje

As economists, we are often asked to calculate the present value of future costs of care. As these calculations are based on the reports of cost of care experts (CCEs), we have become uniquely familiar with the structure and content of those reports.

In this article, we provide a review of the format and contents of cost of care reports, drawn from our experience using those reports as inputs into our own calculations. We anticipate that this review will be of greatest use to:

- members of the bar: as a checklist against which to evaluate the cost of care reports that have been provided for them and their opponents;

- individuals who have recently begun preparing cost of care reports: to provide them with an understanding of how those reports will be used; and

- experienced cost of care experts: as an analysis of some of the complexities that can arise in personal injury actions. For these experts, most of our suggestions will be familiar; but we hope that we raise sufficient questions to make this report of interest to them also.

Incremental Costs

One of the most difficult questions facing the cost of care expert (CCE) is that of distinguishing between those costs that would have arisen had the plaintiff not been injured and those that have arisen as a result of the plaintiff’s injuries. This issue is particularly important when the item required with-accident differs only in quality or type from a similar item that would have been purchased without-accident, for example when the plaintiff now requires a different type of automobile than she would have purchased had she not been injured.

A number of issues arise with respect to incremental costs:

1) When the item required by the plaintiff costs more than the equivalent item for a non-injured person, it is important to be very clear about what is being assumed about the characteristics of the item that would have been purchased by the non-injured person. For example, assume that it has been recommended that a paraplegic purchase a van that costs $45,000 per year. As the incremental cost is the difference between that $45,000 and the cost of the car the plaintiff would have purchased if he had not been injured, it is important that the CCE be able to defend any assumption that has been made about the cost of the latter. Would the plaintiff have owned a Honda that cost $20,000, or a Lexis that cost $50,000? On what basis has that conclusion been reached?

2) Following from the preceding point, it is also important to alert the reader to the possibility that the item that has been recommended by the CCE may be of a different quality than the item the plaintiff would have purchased had she not been injured. Would a $45,000 van, for example, “replace” a $50,000 Lexis? And would the quality of accommodation and food in, say, a nursing home replace the equivalent items in the plaintiff’s own home?

3) An important example of quality differentials arises with respect to the care of injured children. Assume that a child’s injuries are sufficiently severe that the CCE has recommended that professional child care be provided for her – for example, 24-hour attendants. Assume also that the child has a stay-at-home mother; that is, one who would have provided 24-hour care before the child began school. Can it be argued that, as the child would have received 24-hour care in the absence of the accident, the accident has not caused any increment in costs? The answer to this question depends on whether the type and extent of care (i.e. the “quality” of care) that the child now needs exceeds that which would normally have been provided by her parents. For example, during the ten hours that the child normally sleeps, incremental care might be recommended because she will wake more often than normal, or because specialized medical care will be required during those hours. If so, it would be useful if this was specified in the cost of care report. Similar specifications may also be necessary with respect to time that a non-injured child would have spent at school or in day-care.

4) When estimating what the plaintiff would have spent on a category of items if he had not been injured, a distinction must be made between the expenditures that he is currently incurring and those that he would have incurred if he had not been injured. For example, if the accident has reduced the plaintiff’s income, it is quite possible that he will now be living in an apartment with a lower monthly rent than he would have incurred had he not been injured. It is the difference between the rent of the apartment the CCE has recommended (with-accident) and the rent of the apartment he would have lived in (without-accident) that is the incremental cost due to the accident.

5) If the item owned by an injured plaintiff has a longer or shorter life expectancy than the equivalent item owned by a non-injured person, the CCE should identify what that difference is. For example, the van required for a paraplegic might have a five-year use life, whereas the car that the plaintiff would have driven if she had not been injured might have had a ten-year life. In such a case, it would not be appropriate to calculate the incremental cost by deducting the purchase price of the car the plaintiff would have bought from the purchase price of the van, as two vans will have to be purchased for each car.

Variations over Time

The requirements for many items will vary over the plaintiff’s lifetime. It is important to identify when such changes will occur and what their effect will be on annual costs:

1) The plaintiff would have incurred some of the costs of care at various times in his lifetime even if he had not been injured. For example, at age 80, the plaintiff may have hired a housekeeper. Thus, if the CCE had recommended housekeeping services from the date of the accident, for life, the cost that would have been incurred after 80 must be deducted from the recommended expense. In such cases, it would be useful if the CCE was to indicate the age at which the plaintiff would have incurred the stated expense (in the absence of the accident), and what the difference is between the cost of the recommended level of housekeeping and the level that would have been purchased had the accident not occurred.

2) It is important to be clear about variations in expenses over the course of a year – such as due to school holidays and vacations – and over a lifetime – such as because the plaintiff would have started elementary school, entered university, had children, or retired.

3) If the plaintiff will have to undergo surgery in the future, the CCE should indicate how long the recovery period will be and how much the extra costs will be during that period. Also, it will be useful to the economist to know whether the plaintiff will be able to return to work before the end of the recovery period.

Ranges of Estimates

We often find that CCEs provide a range of estimates for the cost of a recommended item. For example, it might be reported that the cost of personal care attendants will vary from $14,500 per year to $21,400. When the CCE wishes to report such a range, we recommend that a reason be provided why a single number would not be appropriate, and the source was of each of the costs in the range be identified. For example, if there is more than one cost, that might be because:

- the CCE received more than one quote, from more than one provider (and if so, why was the lowest quote not chosen?);

- there were different costs for different qualities of the product;

- different costs were appropriate to different potential medical outcomes;

- costs varied among cities in which the plaintiff might live; etc.

Housekeepers and Personal Care Attendants

The CCE report should clearly specify the sources for the hourly costs of individuals who provide housekeeping services, such as housecleaners, yard workers, and maintenance workers. Otherwise the cost of care report may be subject to criticism from experts, such as economists, who are familiar with data concerning the wage rates of these individuals.

Once it has been determined how many hours are required for each type of personal care attendant (for example, nurses and LPNs), there are two basic approaches to estimating the cost of those individuals. The first of these, the agency approach, is to obtain the cost of hiring an agency that will be responsible for all of the specified activities. The second, the hourly wage approach, is to obtain an hourly wage for each type of attendant and then multiply those wages by the specified hours for each type.

Although the latter approach often appears attractive, in the sense that it yields a lower estimate of costs than does the former, there are many reasons to be cautious about use of this approach. First, unless the plaintiff is capable of handling his/her own affairs, the hourly wage approach often assumes that there is a family member who will work without compensation to hire and supervise attendants. But, even if such individuals are available currently, there is no assurance they will be available over the entire course of the plaintiff’s disability. Furthermore, in those years in which family members are available to assist the plaintiff, the courts will generally allow them to claim for the costs of their time, invalidating the assumption that their time is “free”.

Second, the hourly wage approach may not take into account that substitutes will have to be provided for attendants who are ill, wish to take vacations, or who quit without warning.

Third, allowance has to be made for the possibility that attendants will not provide adequate care. This requires that the family or plaintiff have some expertise in both the investigation of the backgrounds of potential hires and in the provision of supervision of existing employees.

Finally, the hourly wage approach would have to provide an allowance for the hiring of additional personnel when emergencies arose. Whereas most agencies will be able to call on their own nurses, and will have close contacts with doctors, ambulances, and hospitals; the plaintiff and his/her family will generally have no expertise in hiring these experts.

Other Factors

We also make the following recommendations concerning the cost of care report:

1) The report should indicate whether GST is included or excluded in the costs recommended.

2) As some items will be GST-exempt while others will not, it is important to distinguish between the two.

3) Indicate whether the costs identified for a particular item are for a different year than the one in which the report was written. For example, if a report was written in 2015, the costs may have been collected from 2014 price lists, or may have been forecasted for a settlement date in 2016. [We generally assume that a report written in 2015 uses “2015 prices”.]

4) It may be advisable, particularly in contentious cases, to have a physician read the CCE’s report and approve the medical expenses, in writing.

Presentation

In addition to the recommendations we have made above, concerning the content of the cost of care report, we also have a number of (minor) suggestions concerning the format, or presentation, of that report:

1) We appreciate it when the CCE provides a summary table in which the annual cost of each item is clearly set out, along with the number of years each cost is to be repeated. We acknowledge that at times, a unit cost, such as medication costs per unit, plus the number of units required over a specific time period is provided. This is just as useful to us, as from this information we can easily determine an annual cost1.

2) If an expenditure is to be made less often than annually – for example, replacement of a car or wheelchair once every five years – it is not necessary for our purposes that the CCE averages the costs over the life of the item. Provide only the replacement cost and the number of years between replacements.

3) On items like cars, houses, and wheelchairs, the cost of care report should, however, provide the annual costs of repair, maintenance, and operation. For a car, for example, provide estimated costs of repairs, of oil changes, and gasoline and tires.

4) The report should be clear about time ranges. For example, it is confusing to say that an item will cost $600 per year from age 25 to 35 and $450 from age 35 to 45, as that leaves it unclear what the cost will be at age 35. We would recommend, instead, that the report say something like: the item will cost $600 per year from 25 to 35 and $450 per year from 36 to 45.

5) There is no need to “round” numbers up or down as economists use spreadsheets for their calculations.

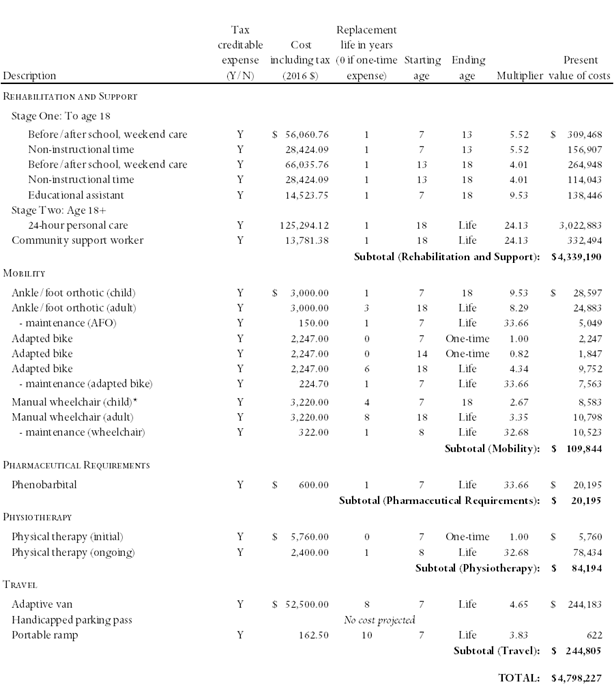

A Sample Economist’s Report

As the economist’s report is always written after the cost of care expert’s report, we suspect that many CCEs will not have seen very many economist reports. As it may help the CCE to understand what types of information are required for an economist report, and in what format that information should be provided, in the table presented below we provide a sample copy of a cost of care calculation for a hypothetical seven-year old male plaintiff.

In the footnote to the table, we have also provided an example of a typical assumption we would make when a range of replacement times has been provided by the CCE.

The columns in the table have the following interpretations:

Tax creditable expense: “Y” in this column indicates that the item can be claimed as a medical expense for income tax purposes.

Cost including tax: the cost of the item, including all taxes.

Replacement life: This column reports the frequency of expenditure. “0” in this column means that the item is purchased only once (there is no frequency); “1” means that the item is purchased every year; “2” means that it is purchase once every two years, etc. For example, under “Mobility” the “Ankle/foot orthotic (adult)” is to be replaced once every three years; the “Adapted bike,” however, is to be purchased only twice, at ages seven and fourteen.

Starting age: The age at which the item is first to be purchased. As the hypothetical plaintiff is seven years old, most purchases begin at seven. However, it is seen, for example, that many items in this table are not to be incurred until the plaintiff is eighteen.

Ending age: Many of the items are to be purchased only over a portion of the plaintiff’s life. Often, as in this case, the costs are different when the plaintiff is a child than when he/she is an adult, and costs may change again when the plaintiff retires or enters a senior’s facility.

Present value of costs: This is the lump sum that would have to be invested today to provide the plaintiff with sufficient funds to replace the stream of future costs in each row. For example, a “Before/after school, weekend care” expenditure of $56,060.76 per year from age seven to thirteen will cost $309,468. This figure varies according to the annual cost, the duration of the expenditure, the discount rate, and the plaintiff’s life expectancy.

Multiplier: Assume that the cost of care expert has recommended an expenditure of $1,000 per year for the next ten years, and that the present (lump-sum) value of this cost has been calculated to be $8,300. If that expenditure was to be doubled, to $2,000 per year over the same time span, the present value of the cost would also double, to $16,600. Alternatively, we can represent this by saying that for every $1.00 of annual costs (over this ten-year span), the present value of future costs will be $8.30. Any lump-sum cost can be obtained by multiplying the annual cost by 8.30. The latter figure is called the “multiplier.” It can be used by the court to recalculate the present value of future costs if the court should conclude that the annual costs are different from those recommended by the cost of care expert.

For example, if the court was to rule that annual before/after school costs were $40,000 (instead of the $56,060.76 reported in the table, the present value would be $40,000 multiplied by the reported multiplier, 5.52, yielding $220,800. [Note: there is a separate multiplier for each starting/ending age combination. Multipliers also differ if a different discount rate or life expectancy is used.]

Sample Cost of Care Calculation for Seven-year-old Plaintiff

* The cost of care expert recommended that the wheelchair be replaced approximately every three to five years. It was also indicated that once the child’s chair had reached its maximum capacity, it would have to be replaced with an adult chair. For the purposes of our calculations, we have assumed that the chair will require replacement every four years until the plaintiff is eighteen.

We would like to thank Stephen Kuyltjes of Rehab Works, Calgary; Sharon Kaczkowski of Kaczkowski Occupational Therapy, Calgary; and Everett Dillman of International Business Planners, El Paso, Texas, all of whom were kind enough to comment on earlier drafts of this article. We are responsible for any remaining errors or omissions.

![]()

Hanoun Multicervical Rehabilitation Unit (MCU) as an adjunct to traditional forms of assessment and rehabilitation. This leading edge, digital technology provides comprehensive objective and valuable cervical functional diagnostic data. It is used to effectively and objectively assess cervical range of motion and neck strength. Together, these measurements quantify the functional capacity of the neck. This differs from other functional capacity evaluations, in that this technology allows us to specifically measure the functional ability of the injured neck. Once functional deficits have been identified and diagnosed, the system can then be used to efficiently and accurately rehabilitate the injured area(s).

Hanoun Multicervical Rehabilitation Unit (MCU) as an adjunct to traditional forms of assessment and rehabilitation. This leading edge, digital technology provides comprehensive objective and valuable cervical functional diagnostic data. It is used to effectively and objectively assess cervical range of motion and neck strength. Together, these measurements quantify the functional capacity of the neck. This differs from other functional capacity evaluations, in that this technology allows us to specifically measure the functional ability of the injured neck. Once functional deficits have been identified and diagnosed, the system can then be used to efficiently and accurately rehabilitate the injured area(s).